"Imitation", exploring China copy culture

Posted in: Uncategorized-640.jpg)

-640.jpg)

%20Photo%20Linda%20Nylind-640.jpg)

Because most of these young factory workers come from a farming background and because joysticks might well become obsolete soon, she proposed to the factory owners that they would allow the joystick makers to work part-time in a nearby farm. She called the experiment ‘Farmification’ – using farming to keep the factory community together when work dwindles continue

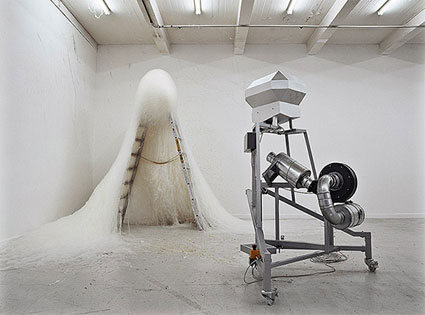

Vortex, by Christoph Hildebrand

More notes about Synthetic Times – Media Art China, an ambitious exhibition about media art running for a few more days at the National Art Museum of China in Beijing. I can’t help but mention an interesting conversation which has just started on the spectre mailing list about whether exhibiting (and blogging about?) media art works in countries ruled by a “problematic” regime is suitable or not.

One of the last two themes, Here, There and Everywhere almost consoled me for all the misery i had to face (no access to either of my own blogs) while in Beijing courtesy of the Great Firewall of China. The works selected in this chapter envision the corollaries of the networked society: the realm where the public and the private sphere merge, the issues of control and anti-control, and the challenges of the Big Brother world.

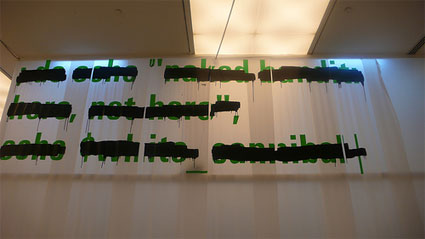

naked bandit / here, not here / white sovereign, by Knowbotic Research, is a critique of the new power structure that global information technologies are bringing about in our world. They are producing new territorial principles of order and new logics of space, as well as constituting forms of transnational power and sovereignty.

An autonomous helium-filled blimp controls and attacks black balloons, the naked bandits, which are kept captive, floating in space. The silver zeppelin, fitted with an orientation camera, is scanning the room, looking for whichever balloon is furthest away.

Image knowbotic research

The harmless and tech-less black balloons are the targets of the sovereign robotic logics which role is to scan, filter, profile, detect and target. Visitors can symbolically intervene in the process. by constructing obstacles in space via their physical presence (serving as additional targets) and making the sovereign space more and more un-navigable.

Meanwhile, coming from above, a mechanical voice repeatedly utters the words “naked bandit / here, not here” in a tone of command that is followed by a another voice representing the “naked bandit”. The sound of the installation specifies the vague status of the prisoner stripped of all rights, who is languishing incarcerated – “here” – in a very real sense. But whose legal existence is suspended – “not here”.

The last chapter The Recombinant Reality presents artworks which embrace the way reality is processed and meditated, revealing new types of reality that reshape our notion of existence while posing questions of epistemological urgency that characterize contemporary experience, in which a Cartesian world view no longer ensures comfort, and syllogistic reasoning finds no suitable dwelling.

Most of Henrik Menné‘s dynamic sculptures are machines or installations are almost organic in the way they transform a material – plastic, wax, metal or stone – into objects.

56L, first created in 2004, consists of solid glue, a fan, iron, a heating element, and an engine.

56L produces a white web of glue. The machine heats up solid glue, which then flows down in thin threads in front of a fan that blows the strings in different directions and forms a surprisingly beautiful sculpture. Although the 56L machine remains the same no matter the gallery where it is displayed, the process of leading to the final glue sculpture is not only subject to change in the environment but is also relying on forces such as gravity and the peculiar qualities of the material chosen. Therefore, the exact dimensions and shape of the final work are almost impossible to control.

The work was probably the most low-tech (what is the correct expression? is it the lowest tech?) one in the show. It reminded me of Michel Blazy’s installations. The artist sets the parameters and the rest has to be left in the hands of a combination of elements.

On view until July 3, 2008 at the NAMOC in Beijing.

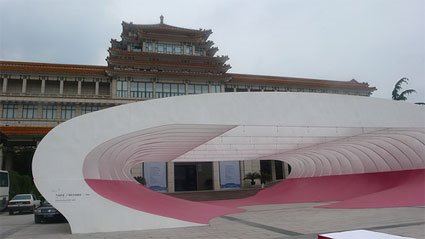

Beijing is the hot city for media art this month. Tonight the Summer Digital Entertainment Jam was inaugurated in a gallery at 798 (the exhibition takes place at Beijing Institute of Fashion Technology), there is the amazing Greenpix media facade and a show which has been dubbed “the biggest exhibition of new media art in the world.” This kind of heavy superlative rubs me the wrong way. The show nevertheless turned out to be an excellent panorama of contemporary media art practice (well, minus my very favourite: activism, China is not exactly big on critics) featuring works easy to understand and engage with even if you’re not a regular of ars electronica festivals. With Synthetic Times – Media Art China 2008, Beijing managed to do what some previous Olympic cities have failed to do (i’m looking at you Torino 2006): taking the Olympics as an opportunity to propose a brave, meaningful, edgy and inspiring art event. I went to the museum twice and was amazed to see so many visitors, from very age range, in the rooms. They were clearly having a good time, asking their husbands or friends to take picture of themselves in front of installations as if these were the Effel Tower and laughing all the way while playing with the works.

Pneumatic Sound Field, by NOX/Lars Spuybroek and Edwin van der Heide, at the entrance of the museum

Synthetic Times – Media Art China 2008 distributes the work of both established and emerging artists around four main themes: Beyond Body, Emotive Digital, Recombinant Reality and Here, There and Everywhere. I had seen many of the projects before but that didn’t prevent me from being delighted to re-discover them in a new context. However, this post will mostly focus on the works i had never

As its title suggest the Beyond Body section explores how artists are adopting electrical, poetical, olfactory or digital paths to extend the physical body. raising questions of subjectivity and the norms of ethical codes.

Back in 2000, Sissel Tolaas embarked on a projects related to fear. She tracked down 20 men from 20 corners of the word, with different background share one characteristic: they are afraid of other bodies for various reasons. These men were asked to carry a tiny electronic device everywhere with them. Whenever they found themselves in a situation where they were likely to be afraid, the men had to place the device under their armpits. The equipment registered the molecules of the respective sweat. This information was then used to simulate the respective sweat in research laboratories, then microcapsulated.

The microcapsulated sweat smells were then integrated into white sheets of papers placed on the surface of a white wall, without any clear borders. The smell could be released only by a gentle scratch ‘n’ sniff.

The other installation i enjoyed was Jean Michel Bruyère‘s The Path of Damastes. 21 white hospital beds, overhung by 21 fluorescent “daylight” tubes, slowly move and perform a ballet.

Each bed is equipped with an electric scissor jack, which permits a vertical movement of the bed from 38 to 81 centimetres up from the ground. It also disposes of motorized control of positioning of the upper body, which permits a roundabout movement of part of the mattress in the angle values from 0 to 70 degrees. These movements can be executed either simultaneously or independently. The 21 beds are linked together via a MIDI system to a PC which commands and synchronizes its programmed movements*. The beds are also animated individually and together they make a vast choreographical ballet. The numerous variations of creaks produced by the lattice structure under the beds in the effort to lift them compose the very music of the piece and its ballet. The beds are neatly aligned in a circular corridor. Once you enter the corridor and walk, beds keep appearing step after step, it almost seems like it will never end again.

The Emotive Digital chapter engages with ideas of the emotions and the often surprising personality that digital life, machines and interactive devices might be imbued with.

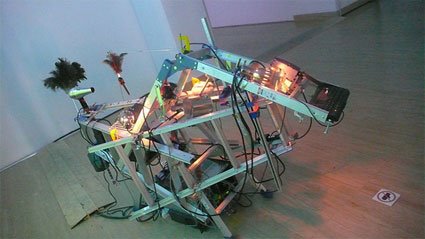

Exonemo (whom Vicente interviewed a while ago) had installed a very successful artwork. Object B VS is a modified first-person shooting game. You are very welcome to play with it and control the action. However, you’ll have to count with a kinetic machine situated on the other side of the screen and assembled from a bunch of household objects, power tools and computer input devices. As wild and chaotic that the machine might seem it does click on the mouse, activate the keyboard and use a pen tablet. Its action hysterically controls an avatar in the game. Try as much as you can, managing to take control over the crazy ugly machine is just a Sysiphean task. The objects’ whimsical actions trigger automatic commands, according to which the game develops.

With Hand Gesture, Wu Juehei explores the way tools shape the way people work and function. Because we spend a lot of time typing on a computer, we got used to a series of “short-cuts” and they came to control our habits of using computers. It is often advised to periodically press (Ctrl + S) in order to save the materials we are working on. Thus, many people would unconsciously press Ctrl + S more than needed without even thinking, as if such action calms their conscious. A simple keyboard had its users forming various and numerous habitual hand gestures.

A keyboard is only a small piece to the puzzle, which kind of new behaviours have came to form part of our unconscious gesture through regular use of the handle of a joy pad, the opening of a cell phone, steering wheel, etc?

My photo set.

The exhibition runs at the National Art Museum of China until July 3.

The latest Neural magazine is available in the best book shops. This issue is dedicated to new media art in China. It contains an essay by Timothy Murray on The Paradox of Chinese Art in the Age of Technology, another by Brian Holmes on China urbanism, industrialization and culture, a review of the 11th Microwave festival in Hong Kong, a presentation of the online project The Great Firewall of China, etc.

The latest Neural magazine is available in the best book shops. This issue is dedicated to new media art in China. It contains an essay by Timothy Murray on The Paradox of Chinese Art in the Age of Technology, another by Brian Holmes on China urbanism, industrialization and culture, a review of the 11th Microwave festival in Hong Kong, a presentation of the online project The Great Firewall of China, etc.

There are book and CD/ DVD reviews, highlights on various musical, artistic or activists projects and as usual, chief redactor Alessandro Ludovico has carried out a series of interviews, this time with 8gg, Yao Bin, Zen Lu, my pals at we-need-money-not-art and i have been been submitted to some parallels quizzes, etc.

Now you’ll know what to answer when someone asks you “I keep reading about contemporary art in China but btw, what is happening in the field of new media art over there?”

Related: 8gg big.

Some choose to embrace art from China, others believe that we should boycott their art as much as the political context. If you follow this blog you’ll know on which side i stand, i can’t get enough of the China art scene. All my China art-mania didn’t save me from being castigated: my blog has been banned in China (euh? what happened here? too much pornography?)

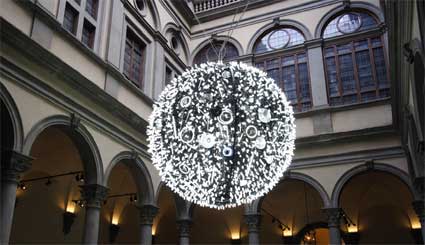

Courtyard of Palazzo Strozzi, Florence

Unrepentant and un-vindicated, i paid a second visit to Florence this year, to check out China China China !!! at the recently opened Centro di Cultura Contemporanea Strozzina (CCCS). The title of the exhibition reflects quite well the plethora of contemporary Chinese art exhibitions which have been sweeping Europe over the past few years.

I recently complained that i keep seeing works by the same elite of artists again and again at every exhibition about Chinese art i happen to visit. Maybe that’s one of the many reasons that explain why i like it so much. It’s a kind of McDonald’s effect, i know before i enter what i’m going to find inside: laughing men, a spat of blood here and there and oh! look! Mao has grown tits!

Artificial Moon, Wang Yu Yang, first seen in Beijng last Summer

However, the Florence exhibition is different on several levels. The first reason jumps at you as you enter one of the first rooms of the exhibitions and discover a series of videos and texts. Each of them document how several exhibitions have recently felt the wrath of the very elastic rules that guide censorship in China. They had to close because some works contained nudity or were judged too “unstable”.

Not only does China China China!!! offer a clear vision of the difficult situation that curators, gallerists and artists alike have to deal with, it also takes up the challenge to give visitors a glimpse of the way Chinese artists echo the complex reality of a country facing an historical change and cultural transformation. To ensure a balanced and somewhat independent view on the “China phenomenon”, the CCCS invited three “insiders”, all of whom live and work in China, are not associated with government institutions, and have worked independently for years. Each of them has a very different but complementary and always critical perception of China’s art scene and its mechanism. The result is nothing like the Chinese art you’ve been seeing around Europe and the USA over the past few years.

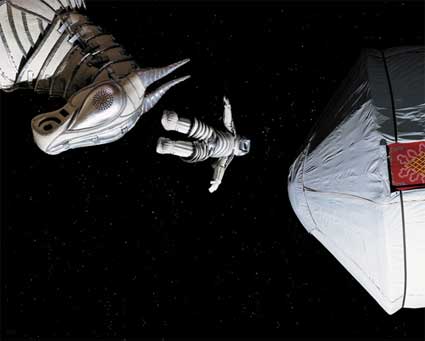

Wu Ershan, Nomadic Plan in Outer Space

Beijing-based artist, curator and founder of the independent Art Lab Li Zhenhua curated the section that i found the closest to my own interests. His approach focuses on common cultural roots between different populations, both between China and its neighbours and, at the more macroscopic level, between East and West.

His contribution in the exhibition revolved around the figure of Genghis Khan, founder of the Mongol Empire, the largest contiguous empire in history. He came to power by uniting many of the nomadic tribes of northeast Asia. After founding the Mongol Empire, he set himself the goal to invade and conquer East and Central Asia. During his life (c. 1162-1227), the Mongol Empire eventually occupied most of Asia.

Wu Ershan, Nomadic Plan in Outer Space

Li Zhenhua chose to invoke his figure as a symbol of the pioneering spirit and communication between civilizations. However, the focus goes beyond the historical past and leads to an analysis of the roots of possible visions of the future of humanity. His section, entitled “Multi-Archaeology”, explores cultural identity, the way individuals are shaped by constant change and reciprocal cultural influences, and thereby the relative value of concepts such as “nation” or “race”.

Wu Ershan, Nomadic Clothes / Space Suit

His selection includes Nomadic Plan in Outer Space is a body of work by Mongolian artist Wu Ershan that comprise, sculptures, installations and photographs along with the costume and photos from the film which represent Mongolians’ nomadic life in the universe. They allude to a non-linear story where the past, the present and the future merge.

Wu Ershan, The first infant who cried aloud is Tiemuzhen, 2008

The art video by Zhao Liang and Shen Shaomin documents the situation on the Chinese border with North Korea and Russia. An analysis of the consequences of the Mongolian invasion by Genghis Khan on Asiatic culture is compared to the impact of modern globalization, in the constant cultural interchange between East and West. In the same time, the works highlight that the Chinese are not the homogeneous, mono-faceted people we often refer to.

Shen Shaomin’s subject is particularly melancholic and poignant. His video, called I am Chinese, takes place in Hongjiang, a village on the border with Russia. During the First World War, when Germany invaded Russia, some Russians on the Chinese border were forced across the Heilongjiang River to Hongjiang Village. Other immigrants joined during WW2 and the October Revolution but the whole Russian community was still struggling to integrate with Chinese society. Things turned really sour during the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) as some of the Russians in the village were suspected of being spies and the village got nicknamed “the village of spies”. In order to be finally accepted by the Chinese, the elders in the Russian community suggested that marriage should be allowed only to pure Chinese in order to mask the Russian origin of their offspring. This of course resulted in genetic modifications and the birth of a mixed culture.

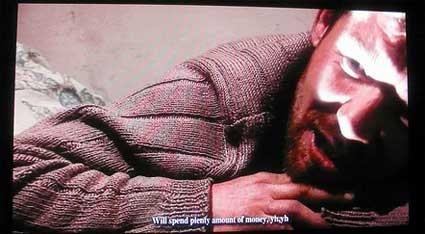

Screenshot from Return to the Border by Zhao Liang, 2005

Equally moving is Return To The Border, a documentary in which Zhao Liang narrates the return to his hometown, Dandong, near the border with North Korea. Until the 1990s, these two socialist states were allies. However, the minute China concluded a trade treaty with South Korea, trade and cooperation was terminated and the people were forcibly plunged into opposite camps. Traveling along the river that separates the two countries, the filmmaker examines what is left of the socialist dreams on both sides of the water.

Video extract:

In his section, Davide Quadrio, director of BizArt Art Centre in Shanghai, developed a very engrossing multi-screen installation entitled 40 + 4 Art is not enough, not enough! Working together with documentary filmmaker Lothar Spree and filmmaker Zhu Xiawen, he interviewed forty different artists in Shanghai and asked them a series of questions about the role of the artist, their relationship with the external world, the social consequences of their work and the international market effects on traditional artistic production modes. The video, edited from 90 hours of film, offers a portrait as much as a dynamic investigation into the fast changing landscape of Shanghai’s art scene. On another level, the film stretches beyond the limits of Shanghai and offers a study of the contemporary art scene in China that reveals what lays beneath the glossy, enchanting and almost uniform surface Westerners are used to see in exhibitions.

The third curator, Zhang Wei, is the director of Vitamin Creative Space Contemporary Art in Ghuangzhou. With Throwing Dice, she composed a mosaique of individual visions of human existence in a constantly changing world. The videos of Kan Xuan, Pak Sheung Chuen and Yang Fudong, Cao Fei’s explorations into Second Life, technological installations by Chu Yun, and paintings by Duan Jianyu offer individual stories that engage the spectator in the discovery of the artistic sensibility in China today.

Tseng Yu-Chin, Who is listening (screenshot)

China China China!!!, Chinese contemporary art beyond the global market is on view at the Centre for Contemporary Culture Strozzina (CCCS), part of the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, until May 4, 2008.

Another date to add in your agenda:

On May 15, Exploded Views – Remapping Florence, a specially-commissioned new installation by Dutch media artist Marnix van Nijs, will premiere at the CCCS.

Notes from the Re-Imagining Asia exhibition at The House of World Cultures in Berlin. The exhibition and other events, curated by Wu Hung and Shaheen Merali, examine how contemporary artists around the world re-invent the image we might have of Asia and the way in which the post-colonial production of knowledge is challenging Euro-centric concepts of art.

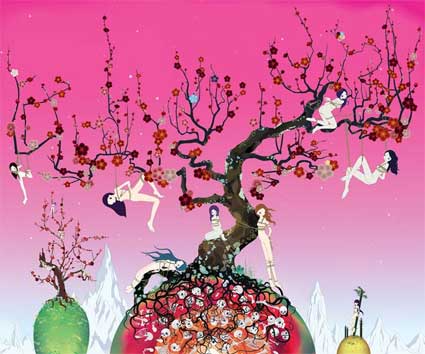

Chiho Aoshima, Japanese Apricot 3 – A pink dream, 2007. (bigger version Galerie Emmanuel Perrotin)

Asian art has reached a point where it is almost too hot to handle. New museums and art biennials are popping up all over the continent, the price paid to get a piece of Chinese art are going through the roof and Indian paintings and installations are exhibited all over Europe. Asian art is now so hype that one might think that another exhibition will just kill the enthusiasm. Well, this one won’t. The works on show have not been selected for the artists’ origins but for their focus on Asia as a space for the imagination. There are Chinese, Indian, Thai and Japanese artists but they are joined by Mexican, Germans and American artists.

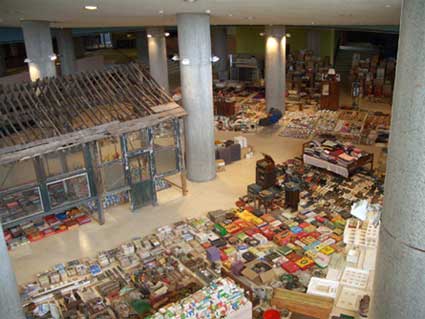

As you enter the foyer of the House of World Cultures, you meet with Song Dong’s installation Waste Not. It is nothing else but his parents’ wooden house, which fell victim to urban planning in China. He reconstructed the house together with its entire inventory, a collection of utensils of all kinds accumulated by the artist’s mother over a period of 50 years and offering a picture of 50 years of material culture in China. It is hard to imagine how several tv sets, so many kitchen utensils, books, old shoes, toys, buckets, plastic bags, ballpoint pens, cupboards, etc could fit into the tiny dwelling.

Image HKW

Song Dong grew up in Beijing. His mother taught him how to make the most of few resources, recycling, re-allocating and saving utensils for future use. The socialist motto was: ‘Waste not’. The shabby borough he lived in has been cleared away for the Olympics a few years ago, but the government neglected to replace the old houses, so there is now an empty area.

On it Song Dong would like to build another wooden house in the traditional style as a call for the preservation of old Beijing.

Besides offering visitors a picture of Beijing life, the installation has relieved his mother of the dead weight of half a century and has done so without making her feel that her hoarding was futile. In fact she fulfilled the role of an artist herself by preparing the show. And each of her mundane and utilitarian objects has been elevated to the status of artwork.

View of the installation at HKW

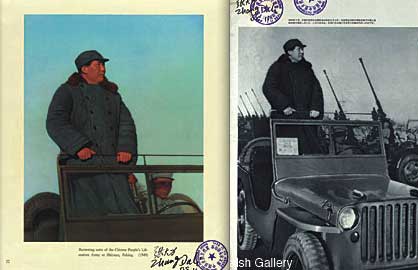

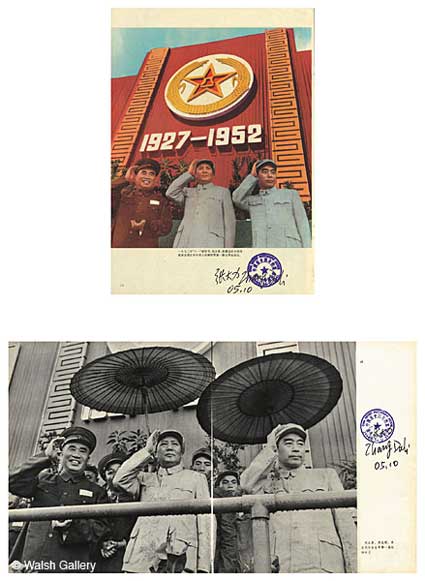

Chairman Mao at Xiyuan Airport, Beijing, March 1949*, 45″ x 25″, Ed. 19, digital c-print, 2006

Zhang Dali‘s “A Second History” was probably the work i found most fascinating. It’s a collection of copies of Mao-era doctored “official” photographs paired with the unaltered originals.

The First Sports Meeting of the National Army, 1952*, 45″ x 25″, Ed. 19,

digital c-print, 2006

The work presents an “archive of the Chinese Revolution” in 3 parts: Mao and the Revolution, Heroes and the Masses, People’s Pictorial Archive. By presenting side by side unaltered photographies from original negatives and the images as they appeared in the media at the time, the installation shows how deliberate distortion of images became an essential mechanism of photo production, a way to satisfy a yearning for an idealized image and a propaganda tool. Long before the arrival of computer and photoshop. The methods used in the editing of these images involve mainly painting: a wrinkle between Mao’s eyebrows vanishes, superfluous figures in the background are erased. (more images of Zhang Dali.)

And in no particular order:

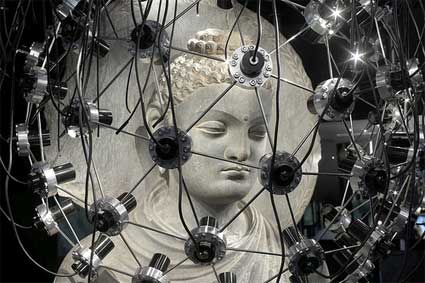

Michael Joo, Bodhi Obfuscatus (Space-Baby), 2005. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging

The Bohdi Obfuscatus (Space Baby) by Michael Joo embodies perfectly the tensions and harmonies between novelty and tradition. In an homage to Nam June Paik, Joo borrowed a Korean Buddha from a local shrine and encased it in a halo of surveillance cameras, Fiber-optic lights cast projections onto flat TV screens while mirrors, mounted on poles that surround the sculpture, reflect images from the video displays, the Buddha sculpture and visitors as they walk around the installation.

Ozone – So Provided by Mizuma Art Gallery. Courtesy of Munteru

Ujino Muneteru was in the house two. I only got to see the Ozone – So installation, a wooden temple turned into a tank and adorned with waste material, such as electric appliances, plush toys, bits of carpet, building materials and books collected around Tokyo by volunteers.

There was also the video of a musical performance Muneteru gave in Berlin. He played with blenders, hair dryers, parts of bicycles, used vinyl discs, turntables, not only was it fascinating to see him handle all this junk but it also sounded surprisingly good.

Shi Jinsong, Na Zha Cradle, 2005

Shi Jinsong‘s razor-sharp line of baby products include a militarized Carriage, a sadistic Cradle and a predatory Walker. Na Zha Baby Boutique (Na Zha is a child warrior deity in Chinese mythology) tries to lure “shoppers” using stainless steel “products” which evoke both luxury and danger.

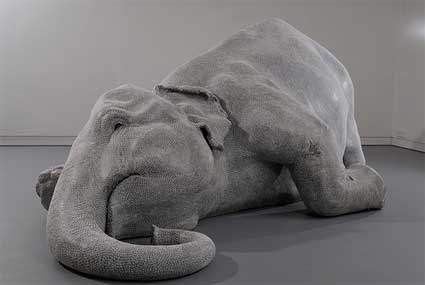

Bharti Kher, The Skin Speaks a Language Not Its Own, 2006. Photo credit:Pablo Bartholomew/Netphotograph.com

Bharti Kher’s bindi-on-fiberglass elephant. The bindi in India is traditionally a mark of pigment applied to the forehead of men and women and is associated with the Hindu symbol of the ‘third eye’. When worn by women in red, the bindi symbolises marriage. In recent times it has become a decorative item, worn by unmarried girls and women of other religions.

Bharti Kher covered her sculpture of a dying elephant in white bindi. The elephant is often regarded in Asia as a symbol of dignity, intelligence and strength. Kher marries the elephant and the bindi to contemplate the effects of popular culture, mass media and consumerism on the culture of India.

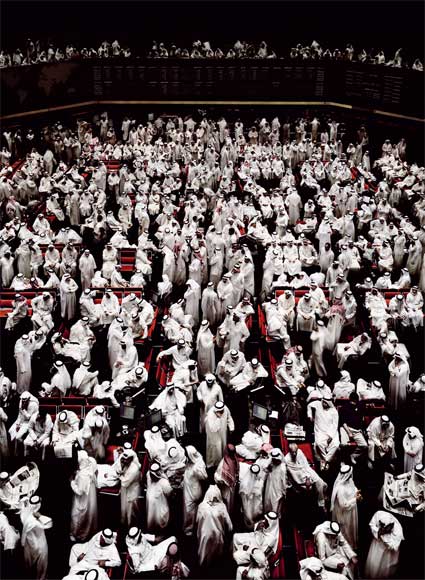

Andreas Gursk, Kuwait Stock Exchange. © Andreas Gursky / VG Bild-Kunst, 2007

Miao Xiaochun, Orbit, digital c-print, ed. of 3, 2005, 85.5″ x 189″ (bigger version of the image)

I took a few pictures. Universe in Universe has more images of the show.

Related: Chiho Aoshima, Mr. and Aya Takano in Lyon.

On Monday i woke up convinced that it would be a good idea to go to the Guggenheim museum and see Cai Guo-Qiang solo show, I Want To Believe. Right from the entrance, i had the suspicion that my brain might not be at its most powerful before 2 pm. What? $18 for an entry? The problem is not that i have to fork them out of my pocket (with the dollar so weak it feels like playing monopoly here) but it is really hard to resist the urge of making any sneaky comment about the consequences of turning culture into a luxury good that only European tourists can afford (didn’t seem to be anyone speaking like a New Yorker when i was there). Oh! Well, there! I spat my comment.

Head On, 2006. Photo by David Heald

I was very curious to see the installation Head On, 99 life-sized plush wolves hurling themselves in a neat row towards and right into a glass panel. That one was almost ok-ish when seen up close but it gained some awe-inspiring power when viewed from afar. The way the row of wolves played with the spiraling architecture designed by Frank Lloyd Wright was pure pleasure. Unfortunately i was not allowed to take any picture and the choice of images from the press kit is a bit lame so you’ll have to take my word for it.

The pièce de résistance was Inopportune: Stage One, nine cars, some of which are suspended from the top of the rotunda, are pierced with blinking light tubes. The installation simulates the freeze-frame trajectory of a car-bomb explosion through the atrium’s void. Now that makes for a very nice poster or postcard. It is impressive in all its flashiness but not very elegant nor particularly interesting.

Inopportune: Stage One, 2004. Photo by David Heald.

More stuffed animals. This time tigers pierced by arrows. Your little nephew would certainly like that one.

Inopportune: Stage Two, 2004. Photo by David Heald

Now there were some artworks which made me happy. Very happy. Such as the re-staging of Venice’s Rent Collection Courtyard, Golden Lion Award at the Venice Biennale in 1999.

The original Rent Collection Courtyard is one of the best-known propaganda works of the Cultural Revolution. The tableau of more than a hundred life-size clay figures was created in 1965 to depict the oppression of peasants by a cruel landlord in pre-Communist China. Copies were exhibited throughout the country during the Cultural Revolution.

One of the guest artisans models clay of one of the figures in the early stages of the installation as Cai Guo-Qiang (left) looks on (image Guggenheim)

10 artisans from China worked on-site during the first two weeks of the Guggenheim exhibit, modeling the 70 life-size clay figures of the New York’s Rent Collection Courtyard (2008). The sculptures are intentionally left unfired, and over time, the clay will crumble.

Images of the original 1965 figures are taped to the ramp walls to serve as references from which the artisans worked (image Gugenheim)

After the conclusion of the New York retrospective, “Rent Collection Courtyard” will travel with to the Guggenheim Bilbao. However, this installation will not appear in the exhibition’s intermediate stop in Beijing during the summer Olympics.

(via)

At the time of the Venice Biennale, the Chinese press raised the issue of appropriation and intellectual copyright and covered the political controversy raised by the widespread belief that Cai was attacking his homeland. A copyright infringement lawsuit against Cai and the Venice Biennale was filed in China by sculptors who participated in creating the original work, but the case was dismissed by the courts.

Actually the more i get back in time, the more i am seduced by the artist’s work. Particularly by his pyromaniac performances.

The Century with Mushroom Clouds: Project for the 20th Century, 1996 (Nevada Test Site). Photo by Hiro Ihara, courtesy Cai Studio

According to Cai, “As a symbol of the progress and victory of science, the ‘mushroom clouds,’ with all their visual impact, have a tremendous material and spiritual influence on human society.” Documented through photos and video, The Century with Mushroom Clouds: Project for the 20th Century is a series of miniature “mushroom cloud” explosions realized at symbolic locations in the United States to “depict the ‘face’ of the nuclear bomb that represents modern-day technology.”

The Century with Mushroom Clouds: Project for the 20th Century, 1996 (Nevada Test Site). Photo by Hiro Ihara, courtesy Cai Studio

The project employed gunpowder placed in small cardboard tubes. Cai detonated the explosions by hand at various locations, including the Nevada Test Site (used for explosive nuclear-weapons tests between 1951 and 1992), Michael Heizer‘s earthwork Double Negative (1969-70) also in Nevada, and Robert Smithson’s earthwork Spiral Jetty (1970) on the Great Salt Lake in Utah.

The Century with Mushroom Clouds: Project for the 20th Century, 1996 (Manhattan). Photo by Hiro Ihara, courtesy Cai Studio

Cai also detonated gunpowder with the skyline of Manhattan in the background.

The Fetus Movement II: Project for Extraterrestrials explosion brought feng shui to the Bundeswehr-Wasser Ubungsplatz military base in Germany. At the site, gunpowder fuse was arranged on the ground in three concentric circles and eight transverse lines to resemble markings for latitude and longitude. To incorporate the feng shui principle that “running water does not rot”, water was diverted from a nearby river into a canal composing the outermost circle.

Fetus Movement II: Project for Extraterrestrials No. 9, 1992. Photo by Masanobu Moriyama, courtesy Cai Studio

Cai positioned himself in the middle on a tiny circular island surrounded by a second canal of river water. He was connected to an electrocardiograph and an electroencephalograph to monitor his heart and brainwaves during the explosion. Sensors were buried around the outside perimeter of the outer circle and attached to a seismograph on the island to simultaneously chart the movement of the earth. A composite print documents the results taken from each instrument before, during, and after the explosion, quantifying the inextricable relationship between man, the earth, and the universe. Video.

Cai Guo-Qiang: “I Want to Believe,” runs through May 28, 2008, at the Guggenheim Museum in New York.