What if society can no longer resist the destructive effects of unbounded capitalism? What if society can no longer resist the devastating power of financial accumulation?

We have to disentangle autonomy from resistance. And if we want to do that, we have to disentangle desire from energy. The prevailing focus of modern capitalism has been energy: the ability to produce, to compete, to dominate. A sort of energolatria, a cult of energy, has dominated the cultural sense of the West from Faust to the Futurists. The ever growing availability of energy has been its dogma. Now we know that energy isn’t boundless. In the social psyche of the West, energy is fading. I think we should reframe the concept and practice of autonomy from this point of view. The social body is unable to reaffirm its rights against the wild assertiveness of capital because the pursuit of rights can never be dissociated from the exercise of force.

When workers were strong in the 1960s and 1970s, they did not restrict themselves to asking for their rights, to peaceful demonstrations of their will. They acted in solidarity, refusing to work, redistributing wealth, sharing things, services, and spaces. Capitalists, on their side, do not merely ask or demonstrate, they do not simply declare their wish: they enact it. They make things happen; they invest, disinvest, displace; they destroy and they build. Only force makes autonomy possible in the relation between capital and society. But what is force? What is force nowadays?

The identification of desire with energy has produced the identification of force with violence that turned out so badly for the Italian movement in the 1970s and 1980s. We have to distinguish energy and desire. Energy is falling, but desire has to be saved. Similarly, we have to distinguish force from violence. Fighting power with violence is suicidal or useless nowadays. How can we think of activists going against professional organizations of killers in the mold of Blackwater, Haliburton, secret services, mafias?

Only suicide has proved to be efficient in the struggle against power. And actually suicide has become decisive in contemporary history. The dark side of the multitude meets here the loneliness of death. Activist culture should avoid the danger of becoming a culture of resentment. Acknowledging the irreversibility of the catastrophic trends that capitalism has inscribed in the history of society does not mean renouncing it. On the contrary, we have today a new cultural task: to live the inevitable with a relaxed soul. To call forth a big wave of withdrawal, of massive dissociation, of desertion from the scene of the economy, of nonparticipation in the fake show of politics. The crucial focus of social transformation is creative singularity. The existence of singularities is not to be conceived as a personal way to salvation, they may become a contagious force.

When we think of the ecological catastrophe, of geopolitical threats, of economic collapse provoked by the financial politics of neoliberalism, it’s hard to dispel the feeling that irreversible trends are already at work within the world machine. Political will seems paralyzed in the face of the economic power of the criminal class.

The age of modem social civilization seems on the brink of dissolution, and it’s hard to imagine how society will be able to react. Modern civilization was based on the convergence and integration of the capitalist exploitation of labor and the political regulation of social conflict. The regulator state, the heir of the Enlightenment and socialism, has been the guarantor of human rights and the negotiator of social equilibrium. When, at the end of a ferocious class struggle between labor and capital – and within the capitalist class itself – the financial class has seized power by destroying legal regulation and transforming social composition, the entire edifice of modern civilization has begun to crumble.

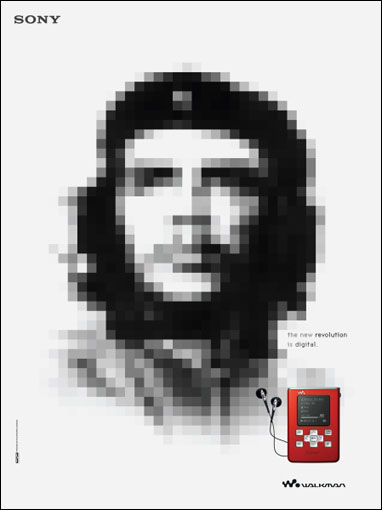

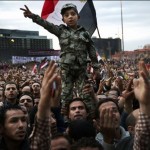

I anticipate that scattered insurrections will take place in the coming years, but we should not expect much from them. They’ll be unable to touch the real centers of power because of the militarization of metropolitan space, and they will not be able to gain much in terms of material wealth or political power. Just as the long wave of counterglobalization’s moral protests could not destroy neoliberal power, so the insurrections will not find a solution, not unless a new consciousness and sensibility surfaces and spreads, changing everyday life and creating Non-Temporary Autonomous Zones rooted in the culture and consciousness of the global network.

The proliferation of singularities (the withdrawal and building of Non-Temporary Autonomous Zones) will be a peaceful process, but the conformist majority will react violently, and this is already happening. The conformist majority is frightened by the fleeing away of intelligent energy and simultaneously is attacking the expression of intelligent activity. The situation can be described as a fight between the mass ignorance produced by media totalitarianism and the shared intelligence of the general intellect.

We cannot predict what the outcome of this process will be. Our task is to extend and protect the field of autonomy and to avoid as much as possible any violent contact with the field of aggressive mass ignorance. This strategy of nonconfrontational withdrawal will not always succeed. Sometimes confrontation will be made inevitable by racism and fascism. It’s impossible to predict what should be done in the case of unwanted conflict. A nonviolent response is obviously the best choice, but it will not always be possible. The identification of well-being with private property is so deeply rooted that a barbarization of the human environment cannot be completely ruled out. But the task of the general intellect is exactly this: fleeing from paranoia, creating zones of human resistance, experimenting with autonomous forms of production using high-tech low-energy methods – while avoiding confrontation with the criminal class and the conformist population.

Politics and therapy will be one and the same activity in the coming years. People will feel hopeless and depressed and panicky because they are unable to deal with the post-growth economy, and because they will miss their dissolving modern identity. Our cultural task will be attending to those people and taking care of their insanity, showing them the way to a happy adaptation. Our task will be the creation of social zones of human resistance that act like zones of therapeutic contagion. The development of autonomy is not totalizing or intended to destroy and abolish the past. Like psychoanalytic therapy it should be considered an unending process.

Franco Bifo Berardi is a revolutionary Italian philosopher and activist. This essay originally appeared in his newly translated book, After the Future.