Objectivities: Photography from Düsseldorf

Posted in: Uncategorized

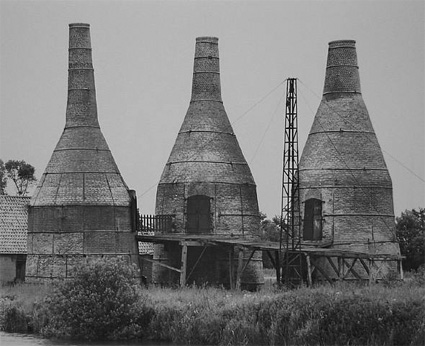

Bernd and Hilla Becher, Lime Kilns: Meppel, 1968, 2005

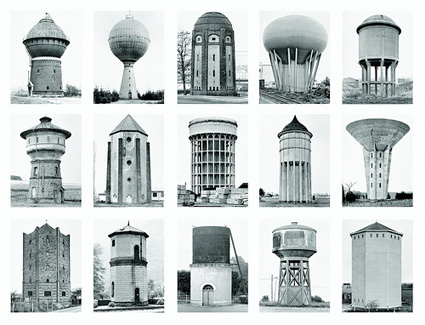

In the mid ’70s, a group of young photographers were studying at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. Their professors were Bernd and Hiller Becher, a couple who had gained fame for taking sharp b&w photographs of industrial archetypes long before it was fashionable to do so. The Becher took pictures like passionate and determined collectors, treating images of water towers, grain elevators, warehouses and other industrial buildings as if they were butterflies that had to be aligned with the utmost care in a catalog. They portrayed the mundane with an unprejudiced and clinical eye.

Becher, Bernd und Hilla, Wassertu?rme/Cha?teaux d’eau, 1999

You might have heard of some of the students, they are among today’s most successful photographers. Actually one of them is said to be the highest-priced photographer alive. While sharing the same tutors at the department of the photography, Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Axel Hütte, Thomas Ruff, Thomas Struth and others have adopted a more personal vision and applied new technical possibilities to the neutral method professed by the Bechers. As a result, their respective artistic paths are exposing greater contrasts than similarities.

An exhibition currently running at Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (which has the least modern website a museum of modern art can dream of) retraces the short and inspiring story of what came to be called the Dusseldorf School of Photography . Objectivités: La Photographie à Düsseldorf presents some 160 works that gives a spectacular overview of the breadth of the photography department of the Kunstakademie from the early 1970s to today.

Türken in Deutschland, Rudolfplatz Köln, 1975. Sammlung Deutsche Bank (via)

Türken in Deutschland, Rudolfplatz Köln, 1975. Sammlung Deutsche Bank (via)

Before turning her lens to sumptuous interiors devoid of any human life, Candida Höfer portrayed the Turkish community living and working in the Germany of the ’70s. She would photograph them in their shops, street gatherings or enjoying a family picnic in the park, letting them pose as if for a family album. It was one of my favourite body of works but i haven’t been able to find much images online.

It is extremely surprising to see how Höfer broke away from the intimate portrays of the Turkish Gastarbeiter (guest workers) to photograph grandiose libraries, museums and other public places, with wow effects, lavish colours but not a single living soul in sight.

Candida Höfer, Goethe-Theater Bad Lauchstädt I, 2006

Laurenz Berges found fame with his photographies of empty constructions as well. First he documented abandoned Russian barracks, back in the early ’90s after the Red Army had left the East of Germany.

Laurenz Berges, Potsdam V (from Räume in Kasernen), 1994

The artist now dedicates his work to the ghost villages of the Rhenish brown coal area, a region between Cologne and Aachen abandoned by whole communities who had to relocate because of the advancing open-cast mining. Berges’ photographs speak of private lives while having a broader, more social relevance.

Laurenz Berges, Vor Vechta, 2008

Petra Wunderlich pays a more direct homage to the neutrality rule set by her tutors Bernd and Hiller Becher. In 1994, she started to document religious buildings in New York. The frontal view makes the buildings even flatter than they already are, the b&w is made more dispassionate by the absence of any human figure and most of the time only the writings on the facade indicate that these are places of worship. In fact, her images reveal that many local synagogues have been converted into Buddhist temples or Baptist churches, while others have been torn down and a few restored (via).

Petra Wunderlich, Brooklyn VI, 2003

Petra Wunderlich, Manhattan X, 1994/2004

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg Bus Stops in Armenia (1997 / 2004) pictures dignified people waiting for public transport vehicles to stop by what is often an inadequate shelter.

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg, Bushaltestelle, Armenien: Echiniadzin-Erivan, 2002 © Ursula Schulz-Dornburg

Ursula Schulz-Dornburg, Bushaltestelle, Armenien: Erewan-Yegnward, 1997 © Ursula Schulz-Dornburg

Thomas Struth gives even more importance to the people in the picture. They become involuntary actors and the setting almost anecdotical. The Museum Photographs series portrays groups of sluggish tourists in shorts, t-shirts and a camera around the neck as they wander around museums. The master pieces behind the visitors are reduced to wallpapers.

Thomas Struth, Museo Del Prado 8-3, Madrid 2005. © 2007 Thomas Struth

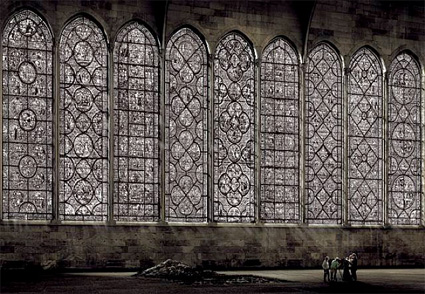

Andreas Gursky might be one of the very few artists who, through manipulations, manage to re-invent historical landmarks like the Chartres Cathedral. One of the minuscule silhouettes at the bottom of the photo is none other than movie director Wim Wenders.

Andreas Gursky, Kathedrale I, 2007

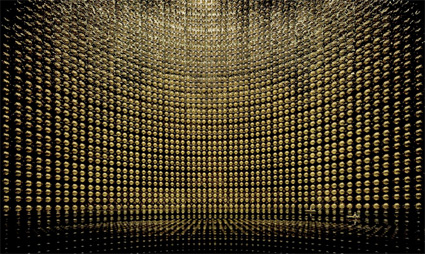

To make stunning Kamiokande, the artist traveled to an underground neutrino observatory in Japan. 1000 meters under the surface of the earth, a tank containing 50,000 tons of ultra-pure water and surrounded by over eleven thousands golden photomultiplier tubes keeps watch for supernovas in our galaxy. You could almost miss two tiny figures in lab uniforms standing on their inflatable rafts. Just like the picture of the Chartres Cathedral, Kamiokande is far more impressive in large-format.

Andreas Gursky, Kamiokande, 2007 © Adagp, Paris, 2008 : Andreas Gursky / Courtesy: Monika Spru?th / Philomene Magers

Thomas Ruff leads the genre to more audacious abstractions, in particular with his jpegs series. Over the past decades, we’ve seen pastoral landscapes and tragic disasters alike succumb to digitization. Their passage through a computer leaves its imprint on our collective memory. But no matter how many photos, we don’t get any more critical or conscious of what lays before our eyes.

jpeg ny02, 2004 © Thomas Ruff. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York

Ruff turns JPEGs culled from the web into abstract works using digital technology. The JPEGs are enlarged to gigantic scale. Seen from close view, the exaggerated pixel patterns leave the image nearly unrecognizable, they acquire an Impressionist patina. The viewer has to stop and take their time to enjoy it, they must watch the images in close-up, mid-range and from far away to fully appreciate them.

On view at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris through January 4, 2009. They have a tiny photo gallery.

Photo on homepage: Bernd and Hilla Becher, (Blast Furnace) Neuves Maisons, Lorraine, France, 1971.

Conscientious has translated an interview with Hilla Becher .

Post a Comment