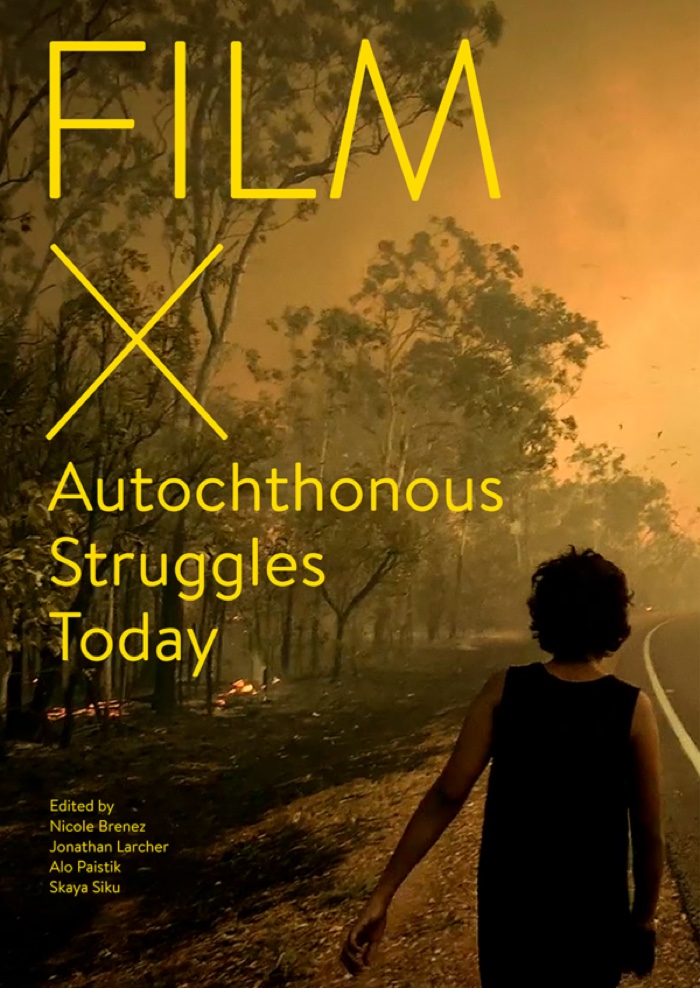

Film X Autochthonous Struggles Today

Posted in: UncategorizedFilm X Autochthonous Struggles Today, edited by Nicole Brenez, curator and head of the department of Analysis and Cinematographic Culture at La Fémis, Jonathan Larcher, researcher at Paris Nanterre Université, Alo Paistik, a researcher focusing on media history and politically engaged media practices & Skaya Siku, an assistant research fellow at the National Academy for Educational Research in Taiwan. Published by Sternberg.

Film X Autochthonous Struggles Today looks at the diverse filmic forms made by and within Autochthonous communities as part of their fights against every form of colonisation, confiscation and contamination of their lands and cultures.

In the book, filmmakers, activists, film curators and scholars share how, since the 1960s and 1970s, autochthonous communities and peoples have integrated films into their repertoire of resistance, along with blockades, sit-ins, peaceful protests and other actions.

Alanis Obomsawin, Sleeping During the Oka Crisis, 1990. Photo: John Kenney (via: Elephant)

Michael Kanentakeron Mitchell, You Are on Indian Land, 1969

The roles played by films in the defence of autochthonous communities’ right to political sovereignty are many.

First, filming responds to the necessity to denounce and raise awareness around environmental injustice, neocolonial domination, economic and political dispossession and extractivist capitalism.

Second, moving images allow communities to redress narratives that have been imposed on them throughout history. Official archives rarely conserve a complete, objective and detailed chronology of the multi-centennial histories of struggles for self-determination. Autochthonous filmic tactics not only fulfil archival and counter-documentation functions, they also help build collective memory and question the history of colonisation and representation. Furthermore, the constitution of this memory shows that their desire for survival and sovereignty is alive. Better than alive, it is interconnected thanks to the rise of what some of the contributors in the book call a “new Indigenous internationalism.” Local communities have quickly realised that other autochthonous people around the world were fighting the same fights: green colonialism, land grabbing, pollution, racial violence and other injustices. This realisation of common challenges has produced solidarity and a collection of moving images that circulate globally.

In their quest to appropriate an art form rooted in state-making and colonialism, Autochthonous peoples have also developed a plurality of cinematographic languages that resist the “monoculturalisation” of otherwise very “biodiverse” and complex cultures.

Christina D. King and Elizabeth A. Castle, Warrior Women (trailer), 2019

Josh Fox, James Spione and Myron Dewey, Awake, A Dream from Standing Rock, 2017

I am going to sound needlessly dramatic here, but Film X Autochthonous Struggles Today has been a lifeline for me. I started the year moping around the house, lamenting the rise of far-right leaders and rhetoric in Europe and seeing only doom everywhere i looked. The book has not only reminded me of my life of freedom and privilege, it has also showed me that people have faced much more arduous circumstances and for much longer. And yet, they never stopped fighting for their rights and for their values. Sometimes with great success. The book details some of these Autochthonous struggles and describes how the camera can become a weapon to fight back against oppression. By revealing to us the strategies and mechanisms of continued resistance, the essays and conversations in the book will hopefully inspire us to take a camera or phone to fight our own fights for human rights, animal rights and the rights of other life forms.

Here are some of the stories and filmic works that i found particularly moving:

Chie Mikami, We Shall Overcome, 2015

Chie Mikami, a journalist working at local Okinawan TV stations, writes about how the national Japanese TV news refused to broadcast any narrative about Okinawa as an island that has been “strong-armed into a cruel existence as a military fortress.” Despite resistance from the local population, military bases and helipads were being built and the government never seemed to be willing to put a stop to the land reclamation of a vast swath of sea for the airfield off Henoko coast. Since these stories of US imperialism never made it to national news, Mikami decided to make a short documentary and broadcast it on the local network. Even though the station kept getting awards for her film, nation-wide TV continued to disregard the military base problem. She then made films for cinema release. One of them, The Targeted Village (2013) shows how one Okinawa village is used as a training target for the US military, with aircraft flying low over Takae, sometimes training their guns on the villagers.

Each of her films denouncing the obnoxious US military presence in Japan’s archipelago was a box office success. And yet, as she writes, little has changed and “Japan continues to impose the burdens of national policy on this weak area on its outskirts.”

John Gianvito, Wake (Subic), Trailer, 2015

Similarly, John Gianvito‘s films expose the consequences and the toxic aftermath of the presence of American forces in the Philippines, revealing the vestiges of colonialism, countless environmental crimes and the subordinated relationship in which the people of the Philippines are placed.

His films break away from classic dialectic filmic grammar of political films. His refusal of Western narrative norms can be read as a political act of resistance.

Dan Taulapapa McMullin, 100 Tiki, 2016-2017

With 100 Tiki, Dan Taulapapa McMullin appropriates Tiki Kitsch images to comment on Western (and Eastern) colonialism of the Pacific Islands peoples from Hawaii to West Papua. The film “borrows” scenes from TV shows, news broadcasts, YouTube amateur videos and even Hollywood movies without asking for the authorisation to do so. The collage of these snippets of videos allows the artist to affirm “his right to piracy, to borrowing, to the artistic disrespect”, a right to resist the commodification of culture and alterity. Tiki, says the artist, is “often mistaken for Polynesian art, but is a European American visual art form […] based on appropriation of religious sculptures of Tiki, a Polynesian deity and ancestor figure.”

The work also interrogates the ownership of Tiki Kitsch images: Who is the rightful owner of the images of Autochthonous peoples? Isn’t the right to piracy an anti-imperialistic as well as an anti-capitalist fundamental right?

Nadir Bouhmouch, Amussu, 2019

Amussu (Movement) is a Moroccan-Qatari documentary by Nadir Bouhmouch and the villagers of Imider in South-Eastern Morocco. From 2011 to 2019, the community occupied a water pipeline leading to a giant silver mine which has been robbing their water and polluting it.

In the detailed and fascinating text dedicated to the experience, Bouhmouch explains how his film crew organised video workshops for the youth of the community, who then filmed some of the scenes and how filming became one of the villager’s many methods of activism, along with poetry, music, theatre and resilience.

Etienne de France, Looking for the Perfect Landscape (video still), 2017

Etienne de France collaborated with members of Tribal Nations in the U.S. to critique the prevalent visual representations of the American Southwest. The vision of the perfect landscapes has been constructed by way of European American colonisation and the continued US occupation, genocides, dispossession and appropriation processes.

The text explains how the collaboration between Indigenous people and an outsider artist has been beneficial to both and has helped deconstruct positions of authority in the course of storytelling.

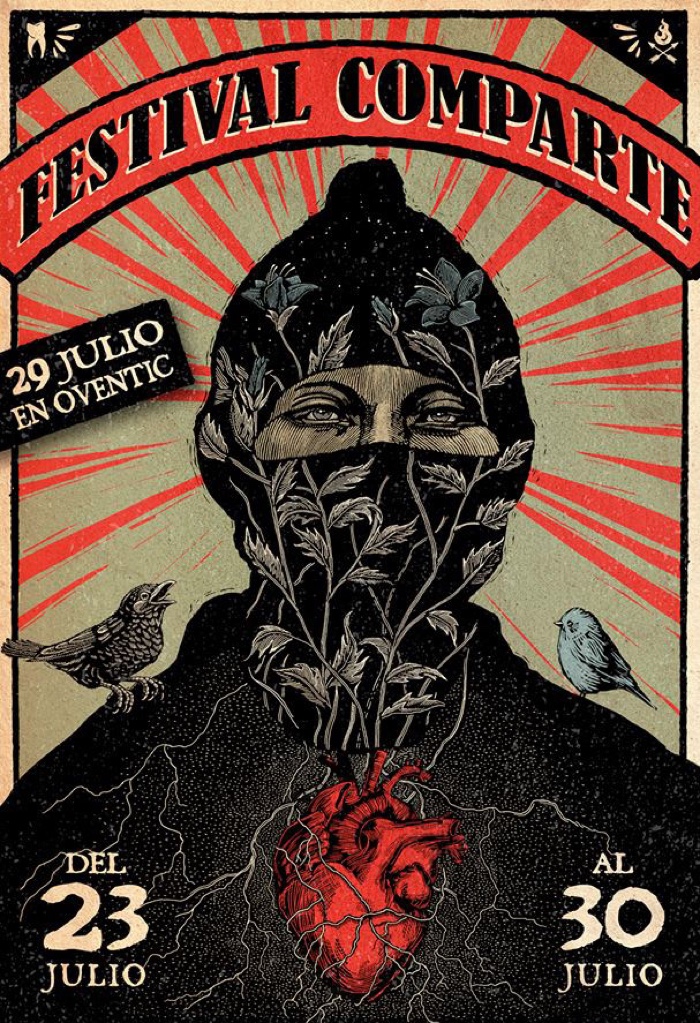

Poster for the festival EZLN CompArte por la Humanidad, 2016, Mexico

Video played a central role in the media tactics of the Zapatistas. It served as a means to self-represent and to counter Mexican state propaganda, which was employed to frame its low-intensity war in Chiapas. The adoption of video technology allowed the members of autonomous Zapatista communities to dissuade soldiers and members of the paramilitary forces, to exchange the knowledge and techniques of political, educational and healthcare-related autonomy between support bases, and to inform the civil society.

Ariel Arango Prada, Sangre y Tierra, Resistencia Indígena del Norte del Cauca (Blood and Earth: Indigenous Resistance in Northern Cauca)

Ariel Arango Prada, Sangre y Tierra, Resistencia Indígena del Norte del Cauca (Blood and Earth: Indigenous Resistance in Northern Cauca)

Sangre y Tierra, Resistencia Indígena del Norte del Cauca (Blood and Earth: Indigenous Resistance in Northern Cauca) is set in northern Cauca, Colombia, where families with power inherited from colonial surnames began to impose themselves on the land and its peoples, maintaining slavery, destroying a significant number of local ecosystems and establishing sugar cane monocultures that extends between the western and central mountain range.

The documentary portrays the resistance of Nasa autochthonous communities against this regime of violence and dispossession and their efforts to recover and work their land.

Lisa Jackson, Mathew Borrett and Jam3, Biidaaban: First Light (trailer), 2018

I also greatly enjoyed the essay that Sophie Gergaud (the director of Ciné Alter’Natif, the only festival in France dedicated to films directed/produced by Indigenous artists) wrote about Indigenous Futurisms. Her text demonstrates that contemporary Indigenous artists have long mastered technological tools to “reflect not merely the future from a linear worldview, but rather non-linear past/present/future spacetime.”

Kim O’Bomsawin, Quiet Killing (Ce silence qui tue), 2018

Aurélie Journée-Duez wrote about the work of Kim O’Bomsawin and the lack of visibility of femicides impacting Indigenous communities in Canada. The report Red Women Rising explains that “Indigenous women represent forty-five percent of homeless women in the Metro Vancouver region

I’d also highlight Perrine Poupin’s essay that charts the local resistance against Moscow authorities’s decision to transform a section of taiga in Northwest Russia into a vast landfill. The project involves transporting by trains millions of tons of waste from Moscow to Shies (Arkhangelsk region) 1,200 km away. Starting from summer 2018, villagers close to the site, and later the inhabitants of the Arkhangelsk region and from the neighbouring Komi Republic, carried out protest initiatives— establishing a camp, monitoring stations around the construction site and organising daily meetings in cities and villages. They used films to document their resistance and denounce “waste colonialism.” Following two years of conflict, Putin gave in to the political pressure and the project was abandoned.

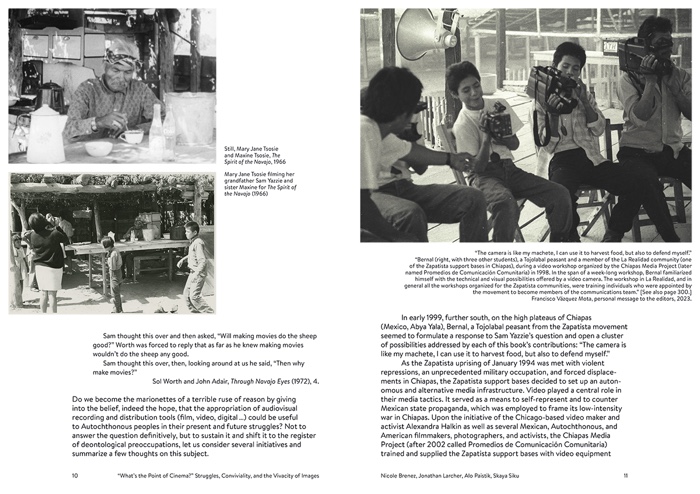

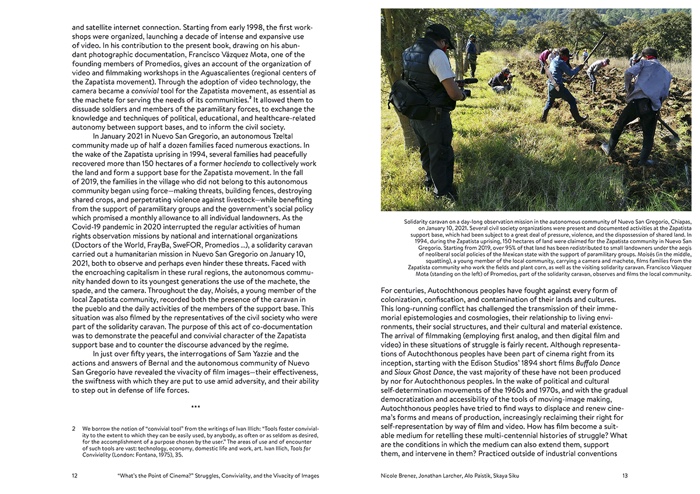

Spreads from the book:

Post a Comment