Alana Hunt. “Everyone talks about stolen cars, and not about stolen Country”

Posted in: UncategorizedLast year, Australia voted in a referendum proposing to enshrine an Indigenous voice in the country’s constitution. The vote would have given Aboriginal and Islander people a chance to directly advise all levels of government on matters that affect their lives. To my extreme shock, the proposal was rejected.

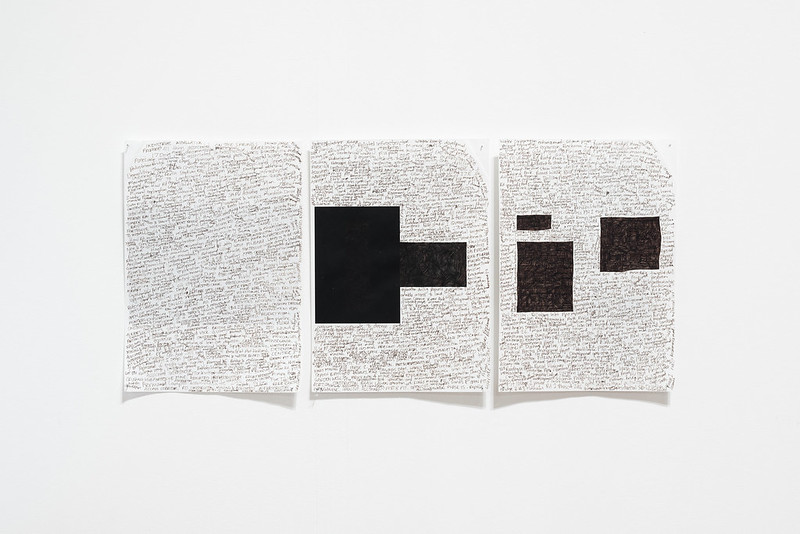

Alana Hunt, Surveilling a Crime Scene, 2023

Alana Hunt, Surveilling a Crime Scene, 2023

Alana Hunt, Surveilling a Crime Scene (Trailer), 2023

Alana Hunt, an artist and writer who lives in Miriwoong country in the north-west of Australia, has long been researching the manifestations of the colonial mindset in Australia. Her work makes the continuing traces of violence and injustice tangible to non-Indigenous people who might not otherwise (want to) see them. Which means that she might not have been as surprised as I was by the outcome of the referendum.

Her film Surveilling a Crime Scene tells the story of Kununurra (the town where she lives) and its surrounds in north Western Australia, charting its colonial history and finding traces of its colonial violence in the fabric of the town: in the landscape, in its economy and infrastructure, in people’s conversation. Using archive images shot in Super 8, all grainy and pastel coloured, the artist how European settlers rearranged the landscape to fit their colonialist expansionist narrative. A mountain was blasted apart, to make way for the town. Then came a large dam that constricts a river and holds the main reservoir. The main objective of the Ord River Irrigation Scheme was to turn Kununurra into a food bowl, a paradise where modern agriculture, irrigation and European know-how would maximise land exploitation. It turned out to be a colossal and costly failure.

Indigenous traditional owners were never consulted. Not did they benefit from the irrigation project.

Tales of imperialism, land grabbing and scars in the landscape, like Kununurra one, are all over Australia. And Australians not only inherits them, they continue them.

Another of Hunt’s recent works, Nine Hundred and Sixty Seven, comments on Section 18 of the Western Australian Aboriginal Heritage Act, a legislation that provides an avenue for mining corporations or landholders to apply to a department committee to destroy, damage or alter registered Indigenous sacred sites. As Hunt explains in the project description,

Since the legislation came into effect in 1972, over 3300 applications have been processed. Only three have ever been declined.

It is the most absurd law, an Aboriginal protection act that gives anyone the permission to ruin culturally significant Aboriginal sites! It’s because of Section 18 of the WA Aboriginal Heritage Act that mining giant Rio Tinto was allowed to destroy the Juukan Gorge, Aboriginal rock shelters dating back 46,000 years.

For Nine Hundred and Sixty Seven, the artist managed to convince Sam Walsh, a former CEO of mining giant Rio Tinto to read out the titles (purpose summaries) of 967 Section 18 applications made between 2010 and 2020.

Alana Hunt, A Very Clear Picture, 2021-2022. Exhibition view Rural Utopias, Art Gallery of Western Australia. Photo by Dan McCabe

Alana Hunt, A Very Clear Picture, 2021-2022. Photo by Dan McCabe

Hi Alana! As a Belgian citizen, I’m fascinated by what your work says about colonisation. In Europe, we can pretend that colonisation belongs in the past, we can even pretend that it did more good than harm. Which is sad and infuriating but possible because the ex-colonies are usually located far away, on other continents. Your work shows what it means to be living on the very territory that Europeans colonise, it shows the daily impact of the settler mentality on Aboriginal communities and the nature of non-indigenous settler communities. I was (naively) expecting that Australians would be more attuned to Indigenous rights, experiences and requests. Your work suggests that this is not the case. Even last year’s referendum saw Australians reject the proposal to recognise Indigenous people in the constitution by creating a body to advise parliament. How do you explain that Australians continue to demonstrate a settler attitude to Indigenous territories and rights? Is it because the Australian land is so vast that it is easier to ignore any inequality and injustice?

Australia also likes to pretend that colonisation belongs in the past. And it is this that my work tries to push against.

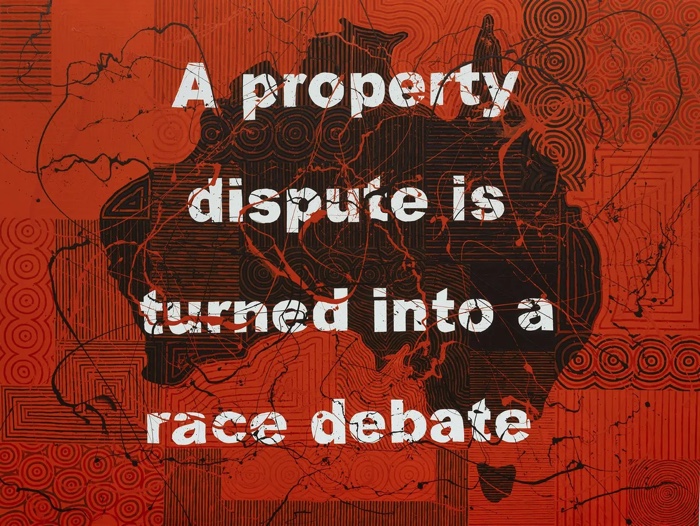

I am trying to point to the fact that colonisation is not only historic, but contemporary. And for non-indigenous people to really feel how our very lives are its tools. To see ourselves more clearly through my work—to recognise the inherent violence of daily life in a settler colony, of the violence in our deceptively simple need for a home, on someone else’s land. There is a painting by Richard Bell that I always return to. It reads: They turned a property dispute into a race debate.

It is not that the land is so vast that inequality and injustice can be ignored. It is that ignorance is convenient. Even useful. And the land theft, at the heart of this, is very profitable. James Baldwin wrote in the 1960s that it is white America’s innocence that constitutes the crime of racial injustice. In 1968, the anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner delivered a Boyer Lecture in which he described Australia’s structural cult of forgetfulness on a national scale, coining the “Great Australian Silence”.

Almost 50 years later, multi award-winning filmmaker and Arrernte/Kalkadoon woman, Rachel Perkins delivered the 2019 Boyer Lecture referencing Stanner with her title: The End of Silence. Rachel went on to lead the campaign for an Indigenous Voice to Parliament. Yet, in 2024, her once hopeful lecture is now haunted by something far more ominous due to the resounding no vote that dominated last year’s referendum. But the struggle continues, hopefully towards more affective political horizons than what the referendum offered anyway. Truly recognising the source of one’s privilege and the consequences of our actions is hard work.

Richard Bell, A property dispute is turned into a race debate, 2019

During your Rural Utopias residency with Spaced, you have been working with the community of Kununurra. What kind of collaboration does that involve with the community? Are they sources of information? Part and parcel of the creative process? Something in between? How much input do they have in the works you develop?

Kununurra was not a “community” I was working with. It was my home. I had lived in this region for a little over a decade on both Gija and Miriwong Countries. I was the first artist in SPACED’s Rural Utopias program for socially engaged art to live in the place I was working—which in some senses, at least to begin, complicated the formula SPACED had become familiar with supporting. It was wonderful and important to me, because the residency that eventuated with the Kimberley Land Council allowed me to deepen work that drew on my life, and what was important and urgent to me, and people dear to me in that place.

As a non-indigenous artist working with an Aboriginal land rights organisation, I was clear from the start that I was not there to extract Indigenous knowledge as such, but to learn from their legal team about the legal processes my non-indigenous culture establishes to enable colonisation. Legal processes the KLC often struggles against and grapples with everyday. Processes that remain opaque to most of Australia.

I wanted to be unobtrusive and tried to slide in and out of the local offices in casual, discreet, every day kind of ways. I refused the format of “artist offers skills-based workshop to unskilled community”, or “white artist photographs themselves smiling with black people”. I wanted to find a way to be quietly useful.

I put my head into paperwork—trying to understand the hypocrisies of the WA Aboriginal Heritage Act (1972), which claims to protect Aboriginal heritage but actually provides a legal pathway for its destruction. I would liaise with the lawyers—particularly Alex Romano and Justine Toohey—in person, via email, and over the phone. I started examining, trying to understand the language my culture used in this dense bureaucracy. It was a language that appeared clean on paper but wrought havoc in the world around me, damaging not only land, but life too. This is what the work came to be about at its core. It’s very personal, but in many ways it has been materialised in a restrained, almost cold kind of way that reflects the bureaucratic system it examines.

Over the years, I shared my work in progress with the KLC and publicly at local events in Broome and Kununurra. I spoke about it casually and formally, and received feedback that fed back into the work. But ultimately the KLC gave me a huge amount of artistic freedom and trust. I think this was brave of them, and really nourishing for me as an artist.

Alana Hunt, Surveilling a Crime Scene, 2023

Alana Hunt, Surveilling a Crime Scene, 2023

Your bio says that both your life on Miriwoong Country in the north-west of Australia and your long-standing relationship with South Asia—and with Kashmir in particular—shapes your “engagement with the violence that results from the fragility of nations and the aspirations and failures of colonial dreams.” What do you mean by fragility of nations? Regarding Australia in particular?

During my MA at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in New Delhi I undertook a course in the history department with the late MSS Pandian on the politics of nation making (and their unmaking). The course really shaped my way of understanding the world, and following that, my creative practice. It exposed me to a whole range of histories and ways of thinking about the nation state. Pandian wove together Agamben, Anderson, Fanon, and Periyar, with closer studies of Tamil and Dravidian political histories, and Kashmir. This was a year after I first started to visit Kashmir, and so I could see and feel all that we were studying playing out in real time in the places around me.

The main sensibility I left that course with is that nations are essentially fragile. They’re persistently trying to hold the diversity of a geographical section of the world together into a unifying narrative and identity—a fragile balancing act. This fragility feeds a nation state wrought by anxiety, and forms of violence are enacted in an effort to hold the state together despite perpetual fragmentation. This violence is not an exception but the status quo. While this course was grounded in South Asia, it helped me understand Australia in clearer ways too, particularly as my life took place on Gija and Miriwoong Countries in the remote north-west of the continent.

How does living on Miriwoong Country influence your work?

Profoundly. Life there has been akin to another university degree, in another world. And those that know me well, understand how personal my work is even when dealing with something as impersonal as legislation and bureaucracy.

It is not only Country, but relationships with Miriwoong and Gija people that have shaped how I understand my own settler culture on their land. I had lived for seven years on their land before I started making work that responded to that context–letting things brew over time is important to me. It is not my place to represent Indigenous culture—I have a lot of personal boundaries around this—and there is a plethora of phenomenal Indigenous artists, Archie Moore’s recent win at the Venice Biennale a wonderful case in point. I try to hone in on my own colonial culture as it unfolds today, focusing on violence people perpetrate but might not initially see—through cultures of leisure and tourism, development, legislation, and increasingly, the idea of home.

Alana Hunt, A Very Clear Picture, 2021-2022. Photos by Dan McCabe

Alana Hunt, A Very Clear Picture, 2021-2022. Photos by Dan McCabe

“Since 1972, over 3,300 applications to Section 18 of the WA Aboriginal Heritage Act have been processed, seeking legal permission to “destroy, damage or alter an Aboriginal site.” Only around three have ever been declined.” This is shocking. i would have imagined that mentalities and sensibilities had evolved a lot over the past 52 years. Have there been attempts to change the way Section 18 functions? How do you explain that this laissez-faire is enduring? How come Aboriginal communities continue to have so little say on matters concerning their cultural heritage?

After Rio Tinto’s destruction of Juukan Gorge hit the news headlines in 2020, Section 18 of the WA Aboriginal Heritage Act, did come under public scrutiny. Though what happened at Juukan Gorge was often seen as an exception rather than the status quo. My video Nine Hundred and Sixty Seven, is an attempt to illustrate that status quo as the 967 applications listed move from mining to things as seemingly benign as footpaths, housing estates, marinas and cultural centres.

Spurred by national and international outrage, the legislation went through a process of reform. For a moment, the political milieu of the last few years looked poised to be a transformative period for the WA Government’s approach to the protection of Aboriginal heritage through meaningful reforms. But as the process was underway, coalitions of First Nations voices stated repeatedly their concerns were not being listened to and their needs were not being met. Regardless, the legislation was rushed through parliament.

Once it was enacted farmers and pastoralists were outraged at what it required them to do, on what they perceived was “their own land”. Due to these very public complaints, the government swiftly reverted back to the old legislation. Ultimately, instead of listening to Aboriginal people the government’s claims of “listening to the community” boiled down to listening to the farmers and pastoralists who successfully fought to protect their right to basically construct fences uninhibited. The new act, while flawed, would have, at least to some extent, spread the burden of bureaucracy to some of these “lower impact” acts—fostering an awareness of the violations inherent in things that otherwise appear to a settler, like a common right. Where things stand now, there has been little more than a return to the status quo that processes over 3300 applications in favour of destruction.

You ask why do Aboriginal people end up having so little say on things that directly impact them. Australian society forges conditions in which there is no real listening, no matter how much “consultation” is performed. I’ve seen these processes drain life from people that are very dear to me. People who should have the right to make use of their life energies in far more self-determined ways.

Surveilling a Crime Scene zooms in on Miriwoong Country to suggest that colonisation is a lasting, ongoing and ordinary violence. It also shows a long history of failures. You kindly granted me access to the film and although i’ve never been to Australia, i found the images and text spellbinding and very moving. But how do Australians react to the film? It must be an uncomfortable video for many of them?

You could hear a pin drop after it premiered in Darwin at the Northern Centre for Contemporary Art… but I am still learning how it will be received more broadly across different parts of Australia and internationally. I am really interested in the circulation or movement of work in the world. In the large, small, and unexpected ways the work we make can strike a chord with other people.

This July, I am going to screen the film at the Kununurra Picture Gardens, in the town it was made about—the town I used to live in. It’s a prospect both daunting and exciting. And so important to me that this work is seen in the place it was seeded. In May, it will also be part of an exhibition at Watch This Space in Mparntwe/Alice Springs alongside paintings by Jack Green, an Aboriginal artist and activist from Borroloola. In a town that has been in the media a lot due to crime lately, the curators of that exhibition have chosen a particularly charged excerpt of the film to promote the show: Everyone talks about stolen care, and not about stolen Country.

As the film reaches audiences—wherever that may be—I hope it is challenging, but also sensitive, precise, and resonant.

What role can art play in helping shift mentalities? Do you articulate your concerns and anti-colonialist ideas outside of exhibitions?

My work is akin to the pores of my skin, so the sentiments infuse and flow through all aspects of my life and in a multitude of ways.

Further to that, exhibitions are often not the primary place that I want my art to be—and that has also been liberating, as I don’t necessarily feel dependent on a gallery system. Galleries can be great, but they’re also quite specific, and certainly aren’t the only place that I want my work moving. In that sense I am also just as interested in publishing, broadcast, public intervention as I am in the potential of a single conversation. I want my work moving in the public sphere and the social space between people—exhibitions can be a means to that, but they aren’t the only means.

I don’t know if art is any more or less able to shift mentalities than say the media, or education, or politics, or religion, or sport, or law, or literature—but it is the language I feel most able to contribute to, and most excited by. All of it is vital, and that’s why collaboration in an anti-disciplinary sense is important too.

Alana Hunt, Nine Hundred and Sixty Seven, 2021

In the video work Nine Hundred and Sixty Seven, Sam Walsh, former CEO of Rio Tinto, narrates the project summaries of 967 applications seeking legal permission to destroy, damage or alter an Aboriginal site via section 18 of the WA Aboriginal Heritage Act between 2010-20. Can you tell me how this work emerged? How did you involve the former CEO of Rio Tinto in the project? Is his participation part of the company’s communication strategy? I’m thinking in particular in statements they made of “serious introspection” and learning from their mistakes?

Via the state government’s website I managed to access the outcomes of Section 18 decisions between 2010-20. Interestingly, after the legislation came under public scrutiny this information was taken off the government’s website. But by then I had already made the video. I produced it in powerpoint with 967 individual slides, using a restrained aesthetic aligned with the aerial font and colour coding of the PDFs I sourced the summaries from. I shared the work in progress with the KLC and the chairman Antony Watson said the work was great, but as it was only text, it was not legible to many Aboriginal people across the Kimberley, especially people like his Father who did not learn to read or write. I realised the film needed oral narration, and knew the narrator needed to be someone who had actually been involved with the submission of one of these Section 18 applications. I contacted a few organisations I knew had submitted a Section 18 application, and asked if any staff would be interested in narrating my film. No one put their hand forward. Someone suggested Sam Walsh, and I managed to source his email. He replied really swiftly. I spoke very frankly about the work, and after a little back and fourth he agreed. Sam was in retirement after a 25 year career with Rio Tinto and had been an important public advocate for the legislation’s reform following Juukan Gorge. I think we just connected at an opportune time.

I like that you raise the company’s communication strategy—further language that needs examination. Weasel words. I have no idea if anyone currently working at Rio Tinto is aware of my work. Either way, I don’t think my video is very redemptive for Sam Walsh or Rio Tinto…it’s more matter of fact.

Any upcoming project, event or field of research you could share with us?

While I am a fairly diligent and hardworking person, over the years I have come to understand that I work in slow, gradual, accumulative ways, where things brew over long periods of time, and in response to the urgencies of life. I used to feel down on myself for being slow, but I’ve learned to treasure what it crafts. I am also very interested not only in time, as in the duration a work takes to make, but in the moments in time a work can encounter and interact with.

From all the work I made around the WA Aboriginal Heritage Act with the KLC, I have also produced three 800 page bound volumes containing my work, writing, and government documents accessed online and via Freedom of Information. One of these volumes is in the KLC archive, but I am really interested in “exhibiting” this artwork/archive in lawyer’s offices or court houses, and libraries. Another form of discreet artistic circulation.

Surveilling a Crime Scene draws on over a decade of life, but the film itself started taking shape over a couple of years, and then it was edited in a few intense months. But now it’s about circulation—how to move that film in the world. And where to move it. One step at a time.

Thinking of encounters with time, the film premiered in Darwin a week before Australia’s referendum on an Indigenous voice to parliament, and one day before October 7 took place. The film is centred on Australian colonial violence and makes reference to Jewish territorial colonialism, which nearly took root near the town of Kununurra. This encounter with these specific moments in time was not planned, infact it felt quite awkward to me, but it is also something worth noting, as it is these things that become part of the work in a sense.

Surveilling a Crime Scene ends with the words:

It is a story about the violence that underpins our deceptively simple need for a home on other people’s land.

Just add water.

I can feel this seeding new work about home. Australia is in the midst of a housing crisis, one that reflects my own experiences of housing insecurity as a child, and now into adulthood. But my role as a settler in a colony, is also central. And Richard Bell’s painting about “property” looms large. As does Hans Haacke’s 1971 work Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971, along with the instagram handle of Jordan van den Berg aka @purplepingers. These are threads, starting to sense each other, and I sense they’ll weave into something, over time.

Thanks Alana!

Related stories: The scars left by electronic culture on indigenous lands, The Funambulist: Forest Struggles, Cold Cases. How temperature is used to assert violence on racialised people, Orchidelirium. Colonialism through the lens of botany, Imperialist narratives around climate. From the 15th to the 20th Century, Tales from the Crust. Portraits of extractive violence and resistance, This Is Not an Atlas. A Global Collection of Counter-Cartographies, Suohpanterror. Propaganda posters from Sápmi, etc.

Post a Comment