Adrián Balseca: solidarity and multispecies resistance against extractivism

Posted in: UncategorizedSince 2008, the Constitution of Ecuador states that nature “has the right to integral respect for its existence and for the maintenance and regeneration of its life cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes”. With the introduction of Article 71 in its constitution, Ecuador became the first country in the world to recognise nature, or Pacha Mama, as a subject with rights at a constitutional level. This new perspective owes a lot to indigenous populations who have contributed to a political and juridical reflection that shifted the focus from an anthropocentric to a biocentric view of rights.

Successful cases of the Rights of Nature implementation in the country saw, for example, the denial of mining permits and a court ruling that the pollution of the Vilcabamba River violated the rights of nature. Unfortunately, as the environmentally damaging activities of extractive industries continue to expand into indigenous territory, civil society groups often struggle to enforce nature’s rights effectively.

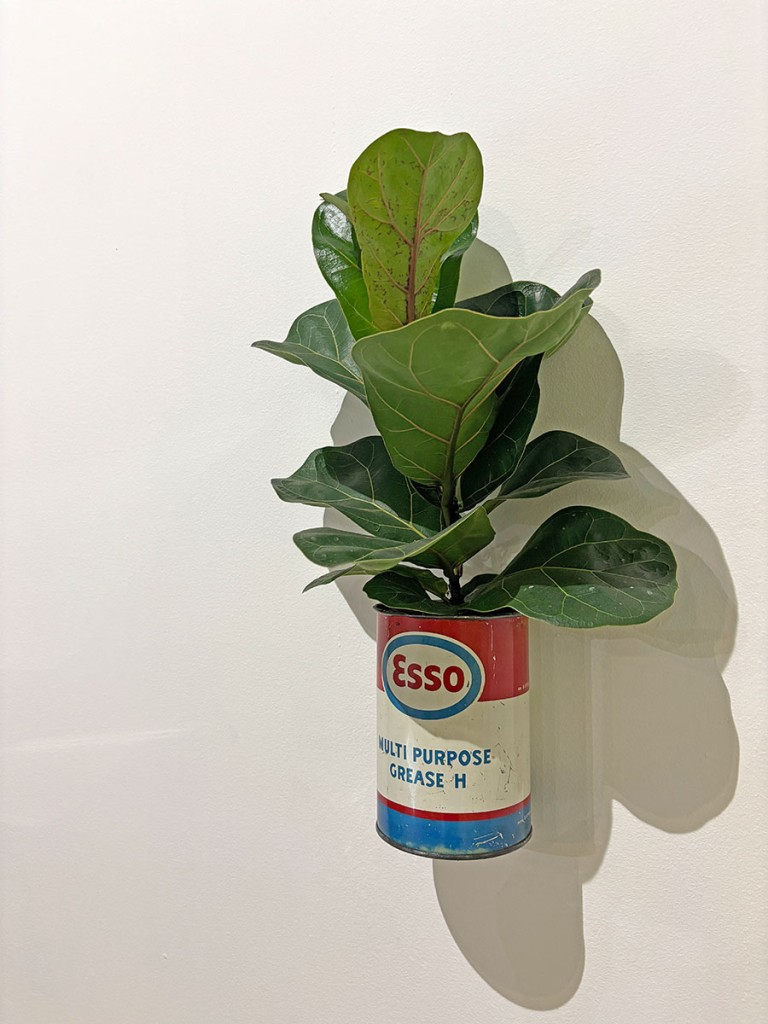

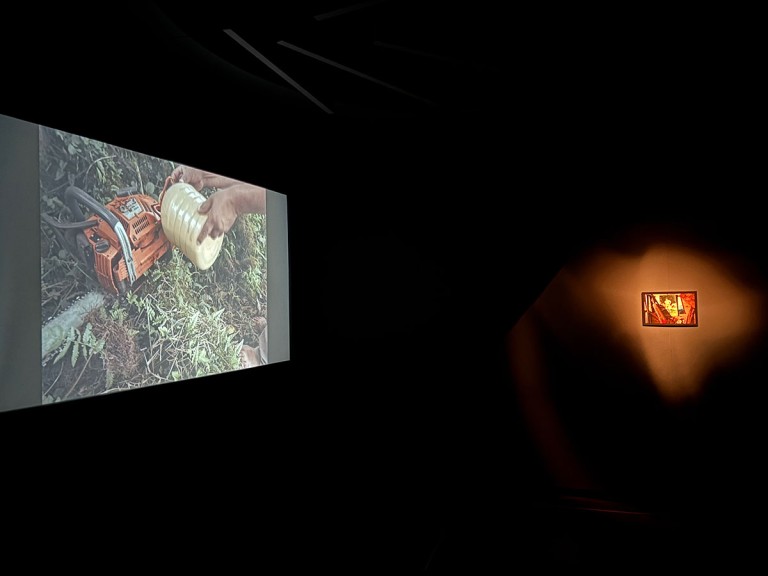

Adrián Balseca, PLANTASIA OIL Co., 2021-ongoing. Exhibition view at PAV Torino

Adrián Balseca, PLANTASIA OIL Co., 2021-ongoing. Exhibition view at PAV Torino

Ecuadorian artist Adrián Balseca has long been investigating the sets of values that impel humans to exploit natural resources in South America at the expenses of the wellbeing of ecosystems and human communities. Cambio de fuerza, Balseca’s solo exhibition at Parco d’Arte Vivente in Turin, takes as its starting point the specificities of Ecuador’s ecosystems to unveil their exploitation and entanglement in international flows of goods and finance. Using archive materials, humour and historical cases, the artist deconstructs colonial narratives and raises questions about the environmental and cultural responsibilities of Western, neo-liberal economies.

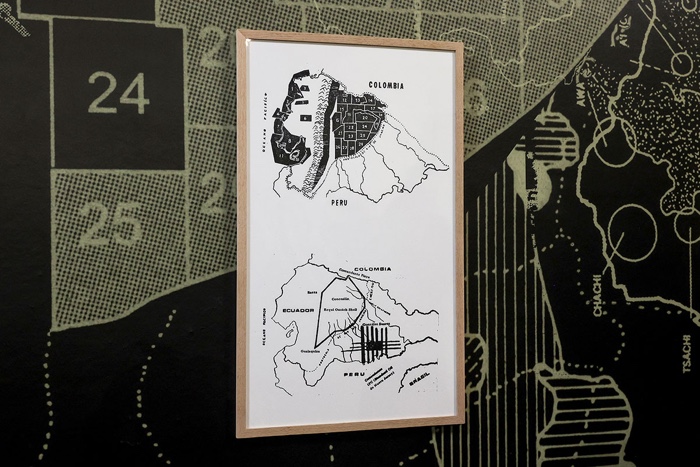

Adrián Balseca, The Unbalanced Land, 2019

Adrián Balseca, Cambio de fuerza. Exhibition view at PAV Torino

The exhibition’s title, Cambio de fuerza [change of power], subverts the slogan “La fuerza del cambio” [the power of change] chosen by Jaime Roldós Aguilera for his electoral campaign towards the end of the 1970s. Roldós was the first president to be democratically elected after the period of civil and military dictatorships. Redirecting the content of the expression, the artist asks how far it is possible to push this political ‘desire’ to convert a rather vague hope for change into a more pragmatic idea, effectively extending it into the field of political ecology.

Adrián Balseca, Medio camino, 2014

Adrián Balseca, Medio camino, 2014

Adrián Balseca, Medio camino, 2014

Balseca’s questioning of society’s priorities was already visible in Medio Camino (Halfway) in which he travelled from Quito to Cuenca in a 1977 Andino Miura, the first motor vehicle assembled in Ecuador. At the beginning of the journey, the artist took out the fuel tank from the vehicle, making him dependent on the goodwill of passersby to complete the 437 km that separate the two cities. It took Balseca 6 days to get to his final destination. The video follows the old pickup truck as it is pushed or pulled by people, a donkey, a tractor or a truck along the Ecuadorian stretch of the PanAmerican Highway that crosses the continent, linking Alaska with Argentina.

The background of the video is a landscape dotted with abandoned petrol stations and an idea of progress that emerged during the ‘petrol boom’ years of the late 1970s and took precedence over nature. Medio camino, however, shows that it’s the solidarity of complete strangers that powers the car, not the extractivist model.

Adrián Balseca, PLANTASIA OIL Co., 2021-ongoing

Adrián Balseca, PLANTASIA OIL Co., 2021-ongoing

<img data-attachment-id="37181" data-permalink="https://we-make-money-not-art.com/adrian-balseca-solidarity-and-multispecies-resistance-against-extractivism/pla_4686/" data-orig-file="https://we-make-money-not-art.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/PLA_4686.jpg" data-orig-size="1200,800" data-comments-opened="0" data-image-meta="{"aperture":"4","credit":"gianluca platania","camera":"Canon EOS R6","caption":"Torino, venerdu00ec 1 novembre 2024nPAV – Parco Arte ViventenCAMBIO DE FUERZA – Adriu00e1n Balseca","created_timestamp":"1730483984","copyright":"","focal_length":"24","iso":"3200","shutter_speed":"0.01","title":"","orientation":"1"}" data-image-title="PLA_4686" data-image-description="" data-image-caption="

Torino, venerdì 1 novembre 2024

PAV – Parco Arte Vivente

CAMBIO DE FUERZA – Adrián Balseca

” data-medium-file=”https://we-make-money-not-art.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/PLA_4686-300×200.jpg” data-large-file=”https://we-make-money-not-art.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/PLA_4686-1024×683.jpg” loading=”lazy” src=”https://we-make-money-not-art.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/PLA_4686.jpg” alt=”” width=”1200″ height=”800″ class=”size-full wp-image-37181″ />

Adrián Balseca, PLANTASIA OIL Co., 2021-ongoing. Exhibition view at PAV Torino

Adrián Balseca, PLANTASIA OIL Co., 2021-ongoing. Exhibition view at PAV Torino

<img data-attachment-id="37221" data-permalink="https://we-make-money-not-art.com/adrian-balseca-solidarity-and-multispecies-resistance-against-extractivism/adrian-balseca-untitled-1987-1992-35mm-film-slide-adolfo-maldonado-clinica-ambiental-part-of-archivo-visual-amazonico/" data-orig-file="https://we-make-money-not-art.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Adrian-Balseca-Untitled-1987-1992-35mm-film-slide-Adolfo-Maldonado-Clinica-Ambiental-part-of-Archivo-Visual-Amazonico.jpg" data-orig-size="700,422" data-comments-opened="0" data-image-meta="{"aperture":"0","credit":"Acciu00f3n Ecolu00f3gica","camera":"Perfection V700/V750","caption":"Digitalizaciu00f3n parcial del archivo de diapositivas de Acciu00f3n Ecolu00f3gica. Procesado en www.elfotolab.com","created_timestamp":"1603955913","copyright":"","focal_length":"0","iso":"0","shutter_speed":"0","title":"","orientation":"1"}" data-image-title="Adrian-Balseca-Untitled-1987-1992-35mm-film-slide-Adolfo-Maldonado-Clinica-Ambiental-part-of-Archivo-Visual-Amazonico" data-image-description="" data-image-caption="

Digitalización parcial del archivo de diapositivas de Acción Ecológica. Procesado en www.elfotolab.com

” data-medium-file=”https://we-make-money-not-art.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Adrian-Balseca-Untitled-1987-1992-35mm-film-slide-Adolfo-Maldonado-Clinica-Ambiental-part-of-Archivo-Visual-Amazonico-300×181.jpg” data-large-file=”https://we-make-money-not-art.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Adrian-Balseca-Untitled-1987-1992-35mm-film-slide-Adolfo-Maldonado-Clinica-Ambiental-part-of-Archivo-Visual-Amazonico.jpg” loading=”lazy” src=”https://we-make-money-not-art.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Adrian-Balseca-Untitled-1987-1992-35mm-film-slide-Adolfo-Maldonado-Clinica-Ambiental-part-of-Archivo-Visual-Amazonico.jpg” alt=”” width=”700″ height=”422″ class=”size-full wp-image-37221″ />

Clínica Ambiental, Archivo Visual Amazónico, 1987-1992

In the middle of the PAV greenhouse, various species of plants grow inside barrels and cans that once contained motor oil and industrial lubricants produced by the Italian and transnational companies such as Shell, Total, Fiat and Agip. The juxtaposition of post-industrial detritus and greenery might look strange to those of us who have a romantic vision of what Amazonia, or nature in general, looks like. Yet, this uneasy coexistence is what characterises most contemporary ecosystems.

Plantasia Oil Co. is a domestic oasis that colonises the waste discarded by the fossil fuel economy, a hopeful vision of a tropical nature that reboots life after the socio-environmental catastrophes that the Ecuadorian Amazon region has repeatedly experienced since the late 1960s, as a consequence of oil extraction by international companies.

The work is accompanied by photographic slides that show archive material found in books published in Ecuador between the 60s and 80s. The discovery in the 1960s of the largest oil reserve in the Amazon catapulted Ecuador into decades of economic prosperity and modernisation. The images illustrate the devastating impacts that foreign corporations were having in different parts of the country. With the extraction of barrels of oil, countless amounts of untreated waste, gas and crude were released into the air, waterways and soil. A brutally high price to pay for local populations and ecosystems.

Adrián Balseca, The Skin of Labour, 2016

Adrián Balseca, The Skin of Labour, 2016

Adrián Balseca, The Skin of Labour, 2016

Adrián Balseca, The Skin of Labour, 2016

Adrián Balseca, The Skin of Labour, 2016

Adrián Balseca, The Skin of Labour, 2016

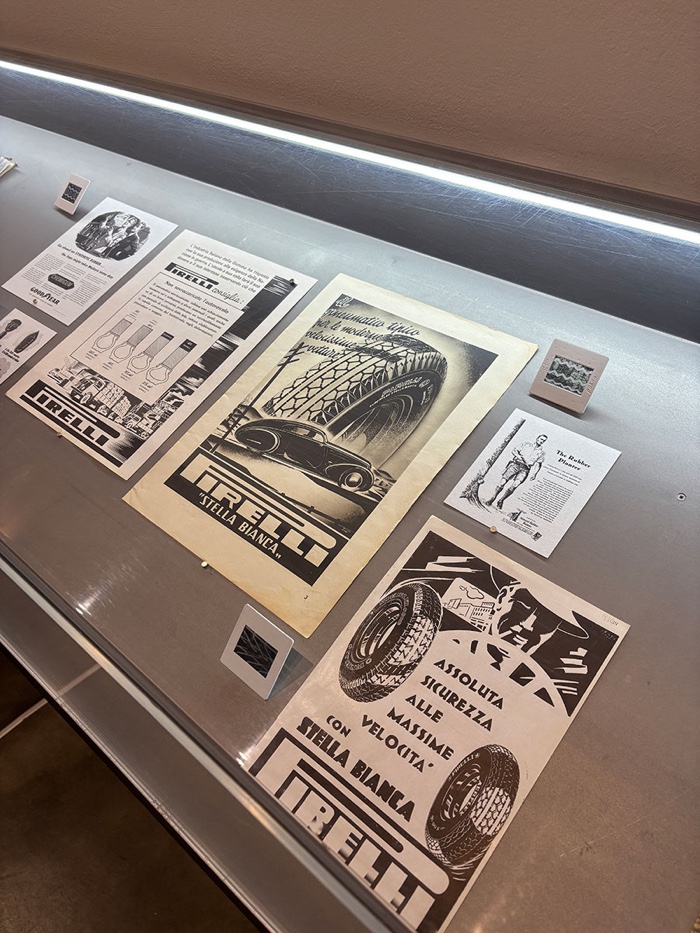

Adrián Balseca, The Skin of Labour, 2016. Installation view at PAV Torino

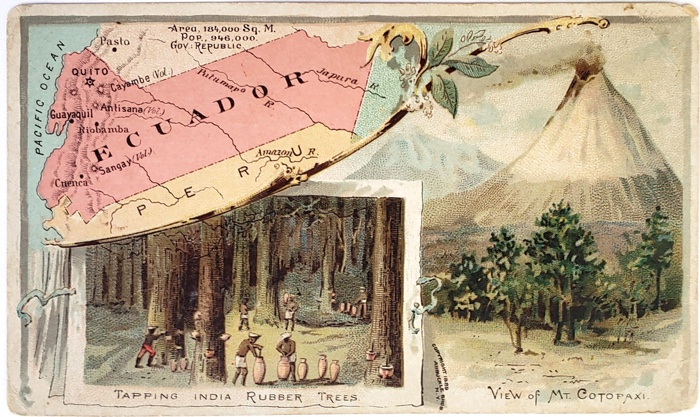

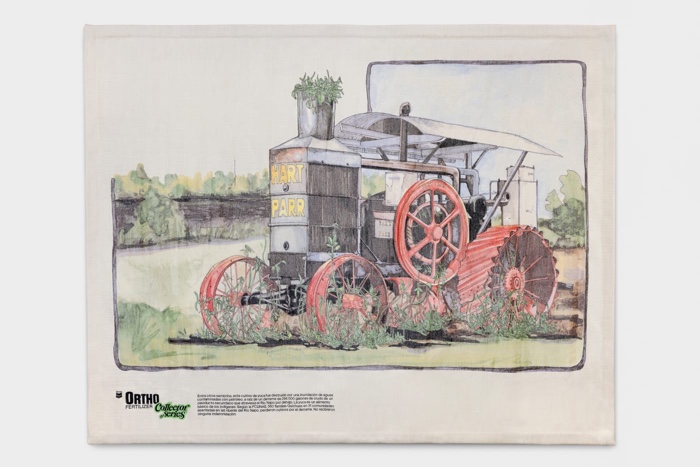

The Skin of Labour is inspired by an endemic forest of Hevea Brasiliensis (rubber plants) growing in Amazonian Ecuador. At the height of the Amazon’s rubber fever, which saw its highest production from the years 1879 to 1912, Europeans expropriated indigenous lands for the purpose of extracting the derivatives of the tree already used by local communities to waterproof clothing and for other ends. People were sometimes enslaved or forced into poorly paid labour to increase production.

The Amazon eventually lost primacy in the world rubber market when the British Empire developed plantations in Malaysia, Sri Lanka and equatorial Africa.

The Skin of Labour features archive material, a digitalised 16mm film, a series of photos and a black glove. The glove is made of butyl rubber, a synthetic rubber derived from petroleum by-products. The object embodies two of the most damaging extractive activities in Ecuador. This hand is also a ghostly presence that stands for the body of the workers but also that of the Amazon. Similar gloves appear in a silent B&W film showing rows of rubber trees, their white sap dripping into the latex gloves. As for the archive materials, they tell the story of the rubber industry from the perspective of the foreign extractive companies. Posters of Pirelli tyres, magazine ads for Goodyear, messages from the U.S. army asking citizens to donate their scrap rubber, children’s booklets narrating the “wonder story” of rubber, etc.

With The Skin of Labour, Balseca challenges the colonial narratives that present the Amazon as a haven for a biodiverse and luxuriant nature but omit the stories of violence caused by the exploitation of this territory in the name of modernity.

Adrián Balseca in collaboration with Segundo Teodoro Ruíz – Project for a portrait (On The Origin of Intriduced Species), 2016. Video still

Adrián Balseca in collaboration with Segundo Teodoro Ruíz – Project for a portrait (On The Origin of Intriduced Species), 2016. Exhibition view at PAV

Adrián Balseca in collaboration with Segundo Teodoro Ruíz – Project for a portrait (On The Origin of Intriduced Species), 2016. Video still

Balseca commissioned a self-portrait from Segundo Teodoro Ruiz, a sculptor originally from the province of Azuay in Ecuador who moved to the Galápagos Islands more than two decades ago. Balseca filmed the entire process from the felling of a Cedrela Odorata tree, an introduced wood species, to the carving of the trunk into a colossal head.

The project investigates the human footprint in the Ecuadorian archipelago and its relation to the species that have been introduced on its territory over time. It reveals the anachronism of scientific categories of endemic and introduced still in use today.

I’ve long been a fan of Adrián Balseca’s work. Thank you Parco d’arte vivente and Marco Scotini for bringing his ideas, with and aesthetic to Turin.

More works and images from the exhibition:

Adrián Balseca, The Unbalanced Land, 2019

Adrián Balseca, The Unbalanced Land, 2019

Adrián Balseca, The Unbalanced Land, 2019

Adrián Balseca, Traducciones crudas 1, 2023

Adrián Balseca, Traducciones crudas. Exhibition view at PAV Turin

<img data-attachment-id="37175" data-permalink="https://we-make-money-not-art.com/adrian-balseca-solidarity-and-multispecies-resistance-against-extractivism/pla_4703/" data-orig-file="https://we-make-money-not-art.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/PLA_4703.jpg" data-orig-size="1200,800" data-comments-opened="0" data-image-meta="{"aperture":"4","credit":"gianluca platania","camera":"Canon EOS R6","caption":"Torino, venerdu00ec 1 novembre 2024nPAV – Parco Arte ViventenCAMBIO DE FUERZA – Adriu00e1n Balseca","created_timestamp":"1730484429","copyright":"","focal_length":"40","iso":"3200","shutter_speed":"0.01","title":"","orientation":"1"}" data-image-title="PLA_4703" data-image-description="" data-image-caption="

Torino, venerdì 1 novembre 2024

PAV – Parco Arte Vivente

CAMBIO DE FUERZA – Adrián Balseca

” data-medium-file=”https://we-make-money-not-art.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/PLA_4703-300×200.jpg” data-large-file=”https://we-make-money-not-art.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/PLA_4703-1024×683.jpg” loading=”lazy” src=”https://we-make-money-not-art.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/PLA_4703.jpg” alt=”” width=”1200″ height=”800″ class=”size-full wp-image-37175″ />

Adrián Balseca, Traducciones crudas. Exhibition view at PAV Turin

Adrián Balseca, Recolector (Estela negra), 2019

Adrián Balseca. Cambio de fuerza, an exhibition curated by Marco Scotini, remains open until 15 February at PAV Parco Arte Vivente, Torino.

Post a Comment