Heard by the Deep. How sound artists reveal the challenges encountered by the underwater world

Posted in: UncategorizedMarine animals sense the world through sound, which travels farther underwater than light. Carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel burning are making the oceans more acidic, meaning that the water carries sound further, leading to even more cacophonous seas and oceans. Engine noise, sonar, seismic blasts, gas drilling, underwater constructions, offshore windfarms and other anthropic noises make it impossible for marine creatures to hunt, detect predators, navigate, mate or communicate. The harmful effects caused by noise pollution range from delayed development to diminished reproduction, stunted growth and disrupted migration paths.

Fara Peluso in residency at MedILS – Mediterranean Institute for Life Sciences in Split. Photo by Aleksandar Topalovic

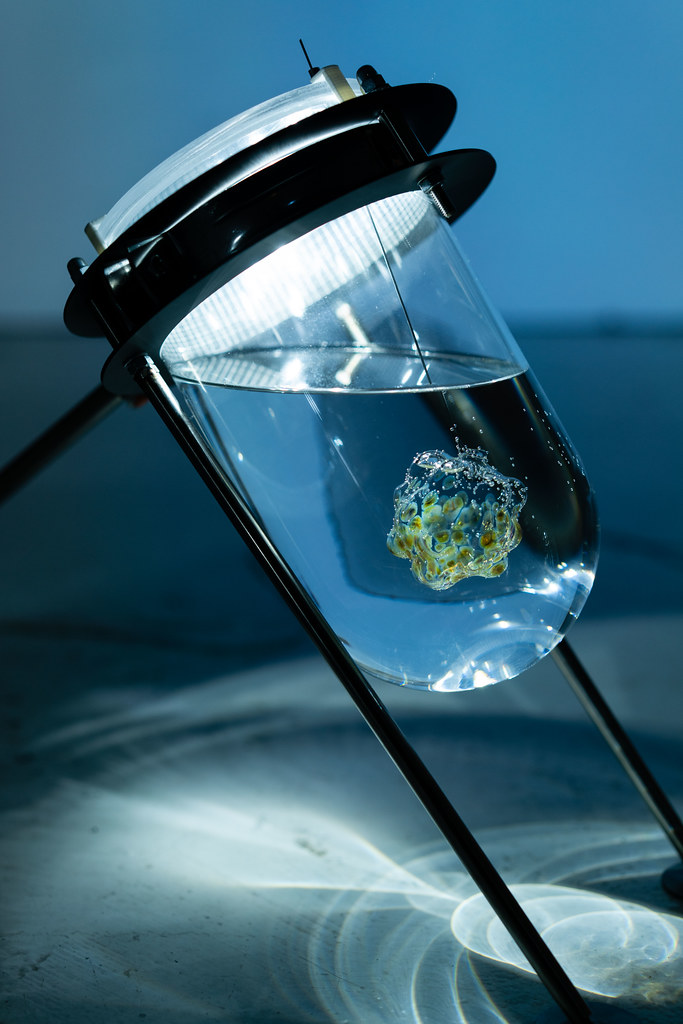

Robertina šebjani?, The Echinoidea future – Adriatic sensing. Photo by Aleksandar Topalovic

Robertina šebjani?, The Echinoidea future – Adriatic sensing

The Heard by the Deep programme, organised by Kontejner in Split (Croatia) a couple of weeks ago, featured artworks, performances and research presentations that demonstrate the power of sound. More than just a medium for communication, sound can be a powerful instrument to raise awareness around the environmental challenges faced by seas and oceans, establish new alliances with sea inhabitants and reevaluate the materiality of the underwater world as well as its semantics.

Split is located on the Adriatic Sea, a region affected by coastal floods and erosion, subsidence (sinking land), salinisation of aquifers, droughts, rising temperatures but also overfishing, bottom trawling, unsustainable forms of tourism and many other anthropic disruptions of fragile marine ecosystems, including most of the sources of noise pollution mentioned above. The participating artists used scientific marine data to shape speculative and thought-provoking scenarios that make us consider with new eyes life conditions in polluted marine habitats, in the Adriatic and elsewhere.

There is more information about the artworks, residencies, workshops and performances on the Heard by the Deep pages. I’ll just present the ones I found particularly engaging:

Stijn Demeulenaere, Zijlijn / Linea Lateralis. Photo by Darko Skrobonja

Stijn Demeulenaere, Zijlijn / Linea Lateralis. Photo by Darko Skrobonja

Stijn Demeulenaere, Zijlijn / Linea Lateralis. Photo by Darko Skrobonja

Stijn Demeulenaere, Zijlijn / Linea Lateralis. Photo by Darko Skrobonja

Stijn Demeulenaere, Zijlijn / Linea Lateralis. Photo by Aleksandar Topalovic

The North Sea water is one of the busiest seas in the world, making it a space permeated with anthropogenic noises: shipping traffic, drilling, oil rigs, wind farms development, fishing, fish farms, etc.

Stijn Demeulenaere spent much of the 2020 year recording sounds in the North Sea, navigating pandemic restrictions, the loudness of anthropic activities and the vicissitudes of the weather at sea.

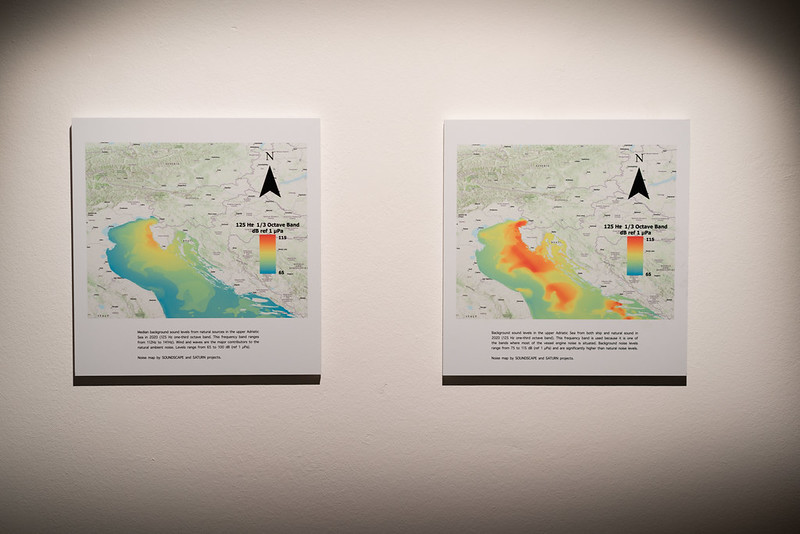

His project Zijlijn / Linea Lateralis investigates the underwater soundscape of the North Sea and in particular the relationship between the biophony (the sounds generated by non-human organisms in a specific habitat) and the anthropophony. Demeulenaere made recordings along the coast of Belgium and then in the Norwegian waters, capturing the soundscape near both the southern and northern shores of the North Sea. The Zijlijn installation gives these sounds -that we otherwise do not perceive- an audible and even physical presence. A row of six speakers faces a line of nine sample tubes containing seawater from the main recording locations. The speakers play a composition based on the recordings from the North Sea. The spectator is his or her own fader, playing with the composition, and the balance between biophony and anthropophony, anew with every listening position.

A series of colourful maps complete the installation. One, dating from 1777, shows the North Sea before motorised shipping. The other two are noise maps that chart the current ambient noise level in the area. Produced by a programme that monitors ambient noise in the North Sea, the maps demonstrate that the sound produced by ships significantly increases the noise levels, compared to the natural noise ones. For the exhibition, the artist added a noise map of the Adriatic Sea, showing that noise pollution is a global phenomenon.

The title of the installation, Zijlijn or Linea Lateralis (lateral line in English), refers to the system of sensory organs in certain fish that detects variation and pressure variations and is connected to their hearing.

Marko Markovi? and Josipa Vujevi? presenting their Mutual Aid Orchestra research at @Razred / Dom Mladih, Split. Photo by Darko Skoponja

Marko Markovi? and Josipa Vujevi?. Photo by Darko Skoponja

Marko Markovi? and Josipa Vujevi? during their residency at the MedILS – Mediterranean Institute for Life Sciences in Split. Photo by Aleksandar Topalovic

Marko Markovi? and Josipa Vujevi? during their residency at the MedILS – Mediterranean Institute for Life Sciences in Split. Photo by Aleksandar Topalovic

Marko Markovi? and Josipa Vujevi? during their residency at the MedILS – Mediterranean Institute for Life Sciences in Split. Photo by Aleksandar Topalovic

Just like Demeulenaere, artist Marko Markovi? and oceanographic engineer Josipa Vujevi? are looking at the phenomenon of noise in the sea. Their research, however, is anchored in the Adriatic sea. The perspective is different too as the objective of their project is to not only understand the communication frequencies among Adriatic Sea mammals but also to create a sound system that could warn them about potential danger zones around them.

Titled The Mutual Aid Orchestra and developed during a residency hosted by the MedILS – Mediterranean Institute for Life Sciences, the work is a continuation of an experiment with orangutans Markovi? did at the Schönbrunn zoo in Vienna two years ago. Monkeys and apes may respond emotionally to music composed specifically for them. Researchers found that non-human primates react emotionally to tunes that incorporated features commonly heard in monkey calls. Melodies inspired by the soothing calls of contented monkeys, for example, relax the animals when it is played back to them. Conversely, primates displayed more anxiety symptoms and increased their movement upon hearing fear music.

Marko Markovi? using music to establish a human-orangutan relationship at the Schönbrunn Zoo in Vienna

Working with a group of musicians in Vienna, the artist played music for orangutans in captivity. It took several months for the artists to establish a relationship with the captive primates. They started by visiting them every day at a certain time, trying to establish contact through gestures and other movements. Over time, it seemed that the apes were expecting their arrival and had perhaps even accepted them as part of their group. They seemed to signal a willingness to interact.

Today’s orangutans are critically endangered by the deforestation and habitat destruction caused by human activities in Indonesia and Malaysia: oil plant cultivation, hunting, illegal trading, etc.

Similarly, mammals in the Adriatic are surviving in a dangerous environment: from rising tourism activities to underground constructions, drilling for fossil fuels, global warming, intense shipping activities and other forms of habitat pollution. Just like the orangutans, sea mammals have nowhere else to go if we pollute and destroy their “home”.

During the residency, the duo used a DIY passive acoustic monitoring to detect the presence of the intelligent sea creatures such as bottlenose dolphins, whales and Mediterranean monk seals, one of the world’s most endangered marine mammals. They also used hydrophones to record all sea sounds and mammal voices. When they detected a sound produced by a mammal, they tried and imitated the frequency and sound and then they sent it back to the sea, waiting for a possible response.

The project objective is to review the effect of sound/music interaction on animal behaviour and its potential in creative communication. Until the noise produced by anthropic disturbances can be drastically reduced, it is our duty to find a way to protect animals and biosphere habitats. Sound, Markovi? and Vujevi? hope, could be used to reduce stress levels in noise-polluted environments. The project is also about creating alliances with other species as a survival strategy to help us all get through increasingly adverse environmental conditions.

More images and works from the Heard by the Deep programme:

Robertina šebjani?, The Echinoidea future – Adriatic sensing. Photo by Darko Skoponja

Robertina šebjani?, The Echinoidea future – Adriatic sensing. Photo by Darko Skoponja

Robertina šebjani?, The Echinoidea future – Adriatic sensing

Fara Peluso, Theca, 2023. Photo by Darko Skoponja

Francisca Rocha Gonçalves, Dis-turbation. Photo by Darko Skrobonja

Marco Barotti, Clams. Photo by Aleksandar Topalovic

Robertina Šebjani?, Tanja Minarik: Line | +1233m -1233m, audiovisual performance @Beton kino / Dom mladih, Split. Photo by Darko Skrobonja

pantea, u-matic, telematique: Fragile fragments, audio-visual performance @Beton kino / Dom mladih, Split. Photo by Darko Skrobonja

pantea, u-matic, telematique: Fragile fragments, audio-visual performance @Beton kino / Dom mladih, Split. Photo by Darko Skrobonja

Photo by Darko Skrobonja

Heard by the Deep is a program created and produced by KONTEJNER within the international project A Sea Change. A Sea Change project brings together partners from four Mediterranean countries: MOMus – Experimental Center for the Arts (GR), NeMe (CY) and Quo Artis Foundation (ES), and realized with the support of local partners MedILS – Mediterranean Institute for Life Sciences and Multimedia Cultural Centre, Split.

Post a Comment